TABLE OF CONTENTS

Message from the Veterans Ombud

Our investigation findings are:

How was the investigation conducted?

Background and factual summary of the investigation

Factual summary of the investigation

Gender-based Analysis+ considerations for the AMA

Annex B – Office of Veterans Ombud fairness definitions

Annex C – Background and investigation

Pain and Suffering Compensation replacing the Disability Award

Why was the Additional Monthly Amount developed?

Additional Monthly Amount – Calculation

Comparing the DA+AMA to the PSC

Why is a female’s AMA amount higher than a male’s?

Annex D – Pain and Suffering Compensation rate table

Annex E – Additional Monthly Amount client statistics

Table 1 – AMA clients as of 31 March 2021, by age

Table 2 – AMA clients as of 31 March 2021 by sex

Table 3 – AMA clients as of 31 March 2021 by age and sex

Table 4 – AMA eligible clients as of April 2021, but not in pay

Message from the Veterans Ombud

I am pleased to present this micro-investigation into the Additional Monthly Amount (AMA) benefit that was introduced as part of the Pension for Life suite of Veterans benefits on 1 Apr 2019.

Prior to 1 Apr 2006, Veterans who applied for compensation for a service-related disability were awarded a non-taxable Disability Pension under the Pension Act. The Disability Pension was a monthly, indexed, lifetime pension that was calculated based on the Veteran’s degree of disability, marital status and number of dependent children. On 1 Apr 2006, the new Veterans Well-being Act changed the way that Veterans were compensated for service-related illness or injury by replacing the monthly Disability Pension with a lump sum non-taxable disability award (DA), and in some circumstances a separate taxable earnings loss benefit (subsequently renamed income replacement benefit). A further change known as “Pension for Life” on 1 Apr 2019 increased the compensation rates and allowed Veterans to receive Pain and Suffering Compensation (PSC) as an indexed, monthly payment or elect to receive it as a single lump sum payment.

Pension for Life created a compensation gap for Veterans who had received a DA between 1 Apr 2006 and 31 Mar 2019 because their lifetime compensation was less than if they had received lifetime monthly PSC instead of a DA. In order to close that gap, VAC developed the Additional Monthly Allowance (AMA). The AMA was automatically calculated for each Veteran who had received a DA between 1 Apr 2006 and 31 Mar 2019, and in essence converted the lump sum already received into a lifetime monthly pension based on the new rates as of 1 Apr 2019.

Not long after the AMA was implemented, we began to receive complaints that male Veterans were receiving less than female Veterans in the same circumstances. What we found is that while actually this difference makes sense, there are other factors about the AMA that are problematic.

First, in order to understand the AMA, we found that the conversion of the DA+AMA into a lifetime monthly pension requires a complex calculation that takes into consideration both the increased rate and the need to account for the initial lump sum over a long period of time. The average life expectancy is different for males and females, which affects the calculation of time to account for that initial lump sum, with the result that the AMA is different for males and females. In fact, in exactly the same circumstances – age and DA amount – a female Veteran will receive a higher monthly amount than a male Veteran. While this certainly seems unfair at first glance, because females generally have a longer life expectancy than males, they have more years within which the initial DA lump sum amount is being accounted for, and thus it makes sense that their calculated AMA is higher.

Next, we considered whether the AMA achieved its purpose in closing the gap in lifetime payments between Veterans who received a DA between 1 Apr 2006 and 31 Mar 2019 and what they would have received had they been awarded PSC and elected the monthly payment. We found that for those Veterans born in 1956 or later, the lifetime value of DA+AMA generally equals PSC when the recipient is 83 years old for male Veterans or 86 years old for female Veterans, but the gap returns thereafter. We refer to this as the crossover point. For both male and female Veterans, DA+AMA is worth less than PSC if the recipient lives beyond the crossover point. Furthermore, the AMA is not recalculated at the crossover point when the initial DA lump sum has been accounted for.

While it is standard actuarial practice to calculate monthly pension values based on differing life expectancies, the AMA is the only VAC benefit that is paid out to individual Veterans on this basis. We believe that continuing non-adjusted AMA payments beyond the crossover point effectively results in discrimination based on sex. The AMA should be recalculated at the crossover point, which is generally 83 and 86 for male and female Veterans, respectively, born in 1956 or after to exclude the life expectancy accounting factor and to achieve parity with PSC.

In summary, the AMA as it is constructed is fair, but only up to the age at which the initial lump sum DA is accounted for. Because there is no adjustment for life expectancy nor for parity with PSC at that point, two things occur that are unfair:

- The differential rate in the AMA between male and female Veterans is no longer justified on the basis of the actuarial calculation resulting in a monthly payment that discriminates on the grounds of the sex of the Veteran; and

- The gap between lifetime monthly PSC recipients and DA+AMA recipients begins to increase.

I am therefore making the following recommendation to the Minister of Veterans Affairs and Associate Minister of National Defence:

Correct the financial unfairness between the two benefits at the crossover point. Increasing the Additional Monthly Amount payment to the same rate as the Pain and Suffering Compensation payment for Veterans who live beyond their crossover point would be one way of achieving this.

Veterans Ombud

Colonel (Retired) Nishika Jardine

Executive Summary

From 2006 to 2019, Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) financially compensated Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members and Veterans for service-related disabilities via the Disability Award—a lump sum payment. In 2019, VAC replaced the Disability Award with the Pain and Suffering Compensation—a monthly payment for life.

|

Disability Award (DA) – a financial benefit paid to a member or a Veteran who establishes that they are suffering from a disability resulting from (a) a service-related injury or disease; or (b) a non-service-related injury or disease that was aggravated by service. The DA was paid as a lump sum, or it could be divided into a series of equal payments. Pain and Suffering Compensation (PSC) – a financial benefit paid to a member or a Veteran who establishes that they are suffering from a disability resulting from (a) a service-related injury or disease or (b) a non-service-related injury or disease that was aggravated by service. The PSC can be taken as a lump-sum or as a monthly payment for life. The PSC replaced the DA on 1 April 2019, with the implementation of the Pension for Life family of benefits. |

For more than 45,000 Veterans, the Disability Award received was less financially valuable than the Pain and Suffering Compensation would have been, had it been available at the time. To compensate these Veterans, VAC pays them an Additional Monthly Amount every month. The Additional Monthly Amount aims to make the lifetime value of the Disability Award and Additional Monthly Amount together comparable to that of the Pain and Suffering Compensation.

Veterans questioned why the Additional Monthly Amount is higher for females than for males, and they brought their questions to the Office of the Veterans Ombud (OVO). We started an investigation to determine if the differences were fair.

Our investigation also compared the combined Disability Award and Additional Monthly Amount to the Pain and Suffering Compensation, which required complex actuarial calculations.[1] We hired an independent actuary to model and compare the lifetime value of each benefit using the same data and assumptions VAC used to develop the Additional Monthly Amount.

Our investigation findings are:

- The lifetime value of the Disability Award and Additional Monthly Amount generally equals the Pain and Suffering Compensation when the recipient is 83 years old for males or 86 years old for females. We refer to this as the crossover point.

- For both male and female Veterans the Disability Award and Additional Monthly Amount are worth less than the Pain and Suffering Compensation if the recipient lives beyond the crossover point. The Additional Monthly Amount is not adjusted to account for this.

- The Additional Monthly Amount is higher for females than for males because the calculation accounts for females’ statistically longer lifespan.

- It is standard actuarial practice to calculate average lifetime pension values based on different life expectancies for males and females. However, the AMA is the only VAC benefit that is paid out to individual Veterans on this basis.

- Continuing to pay male Veterans, who live beyond their expected lifespan – the crossover point – a lower Additional Monthly Amount than female Veterans would then be treatment based on sex alone, not just on the statistical differences in life expectancy. We believe this is unfair.

|

Crossover point – The age when the discounted Pain and Suffering Compensation (PSC) becomes greater than the Disability Award + Additional Monthly Amount. This is also the point where the monies (DA) for which the theoretical offset period was created have been repaid. |

To prevent unfair treatment of older Veterans, the OVO recommends that the Minister correct the financial unfairness between the two benefits at the crossover point. Increasing the Additional Monthly Amount payment to the same rate as the Pain and Suffering Compensation payment for Veterans who live beyond their crossover point would be one way of achieving this.

Purpose of the investigation

The OVO initiated this investigation to respond to the following questions:

- How does total lifetime compensation of the DA[2] plus the AMA (DA+AMA), compare to the total lifetime compensation of the PSC[3] monthly amount?

- Why are AMA payments greater for female Veterans[4] than for male Veterans, for the same percentage of DA?[5]

The AMA is a non-taxable monthly payment to members and Veterans who previously received a DA but would have received a higher amount under the new PSC benefit if a monthly payment option existed when they received their DA prior to 1 April 2019. This reduces the lifetime payment gap between the DA and the PSC. As of 31 March 2021, there were 45,870 AMA recipients.[6]

How was the investigation conducted?

The OVO investigates systemic issues using a fairness model with three components: fair treatment, fair process, and fair outcome (Annex B – OVO Fairness model).

In this investigation, we reviewed the applicable legislation, VAC policy, and records of discussion from VAC stakeholder consultations, to determine if the AMA benefit meets the policy intent as written in legislation. We also contracted an independent actuary to build a computer model to compare the lifetime compensation of the DA+AMA to that of the monthly PSC. The model uses standard actuarial principles to predict the future revenue streams of both benefits,[7] and the age, if the Veteran survives, when the cumulative PSC revenue becomes greater than the DA+AMA — henceforth called the crossover point in this investigation. The AMA calculation sets up a period to theoretically repay the amount above and beyond the monthly PSC payments that would have been paid. The crossover point is also the point where these repayments would theoretically expire.[8] To explain the AMA calculation, we used the scenario from the VAC Pension for Life webpage[9] of a male Veteran (Hasan) and a female Veteran (Anna) each with 40% DA (see Annex C – Background and investigation). The VAC example explains the calculation as an overpayment that is recovered over the lifetime of the Veteran.

This investigation did not include a comparison of the lump-sum PSC payment, because the lump-sum option is a choice available to PSC recipients. DA recipients did not have a choice between a lump-sum and a payment for life.[10]

Background and factual summary of the investigation

Background

On 1 April 2019, VAC implemented the Pension for Life (PFL) family of benefits. In PFL, the PSC benefit replaced the DA. The DA and the PSC are both financial compensation for a disability, and the amount paid is based on the percentage of disability—regardless of sex (see Annex D for PSC rate table[11]). The AMA benefit takes into consideration the amount of the DA previously paid and the amount of monthly PSC they would have received. The difference is converted to an amount paid monthly, over the course of the recipient’s life.[12] The official VAC AMA policy statement is as follows:

“The policy intent of the AMA is to provide a monthly payment to members and Veterans who were previously paid a Disability Award, but would have received a higher amount under the new Pain and Suffering Compensation (PSC) benefits program, if it existed prior to 1 April 2019, when they received their Disability Award.”[13]

Factual summary of the investigation

The details of the AMA investigation, including how the AMA is calculated, can be found at Annex C – Background and investigation. A review of the information collected, shows that:

- In VAC stakeholder meetings, VAC officials told participants the intent of the AMA was to ensure that those Veterans who had received a DA would not receive less than the PSC.[14] [15] This is a deviation from what is written in the VAC policy document.

- The AMA benefit was well designed from a service delivery perspective. There was no need to apply for the AMA. VAC proactively reviewed the files of all DA recipients to determine eligibility prior to PFL coming into force on 1 April 2019 and then facilitated payment once contact details were confirmed.

- The AMA is a complex calculation and includes an annuity factor which contains male/female mortality rates, inflation, and interest rates.

- The AMA is difficult to calculate and understand without an in-depth understanding of actuarial calculations. The VAC examples do not provide the annuity factor, all the necessary information to understand what goes into the annuity factor, or its component parts, necessary to calculate or replicate its results. This information is also not found in the Veterans Well-being Act or Veterans Well-being Regulations.

- The AMA calculation assumes that the Veteran received the PSC from the beginning, but considers that the DA has to be repaid over the expected lifetime of the Veteran, while still receiving a monthly payment. Once the repayment is theoretically repaid (crossover point), the AMA payment is not adjusted for male or female recipients to the full PSC amount.

- The male/female mortality rates, which are included as part of the annuity factor, cause the female AMA amount to be higher than the male amount for the same DA percentage. This difference is because women statistically live longer than men[16] and will have a longer theoretical offset period to repay the DA credit.

- The use of the male/female mortality rates in the AMA calculation resulting in different AMA payments for males and females is in accordance with standard actuarial practices for calculating pension values. However, no VAC benefit is paid out to Veterans at different amounts based on the different life expectancy of males and females.

- The OVO actuary model calculates the lifetime revenue streams for the AMA and the PSC generally intersect at 83 and 86 years of age for males and females respectively.[17] [18]

- At the crossover point, PSC recipients become better off financially than AMA recipients, even though for AMA recipients, the monies for which the theoretical offset period was established have been repaid.

- When males reach the crossover point, their AMA continues at a lower amount than the female amount, even though the reason for the different male and female amounts is no longer justified (because the DA credit has been theoretically recovered). This financially disadvantages male compared to female Veterans, based on sex and not the statistical differences in life expectancy.

Analysis

Lifetime revenue comparison

The AMA calculation makes the DA+AMA amount the actuarial equivalent of the PSC monthly amount, while accounting for a theoretical offset period to recover the DA already paid. In VAC’s response to the OVO’s written questions, VAC advised the policy intent of the AMA was not to make the DA+AMA equal to the PSC but to make the differential as small as possible. This objective is accomplished with the AMA as calculated, up to a point. This is also reflected in what VAC told its advisory groups in PFL briefings, that “The intent of the Additional Monthly Amount was to ensure that those Veterans who had received a disability award would not receive less” (Veterans Affairs Canada, 2019).[19] [20] If an objective was to ensure the two benefits were as close as possible, or DA recipients did not receive less than PFL recipients, it is surprising that the AMA does not increase, to the same amount as the PSC, when the theoretical offset amount is repaid at the crossover point. Up to the crossover point the AMA achieves its aim, after the crossover point is where AMA recipients are financially less well off in relation to PSC recipients. Also, after the crossover point male AMA recipients continue to receive a lower AMA amount than females, this treats men and women differently, based on sex.

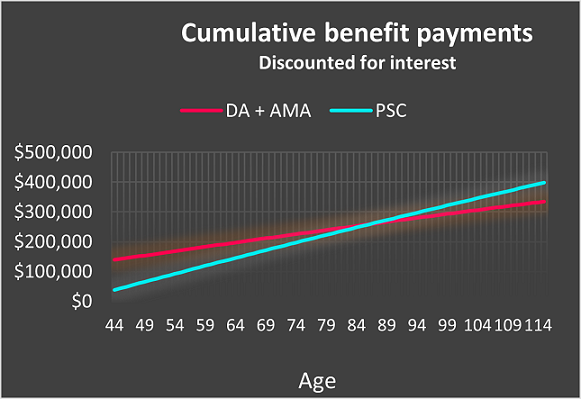

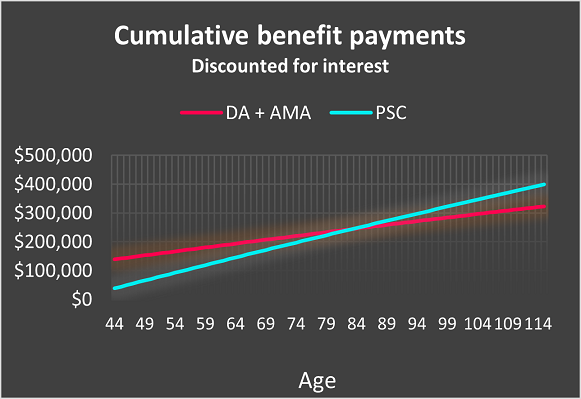

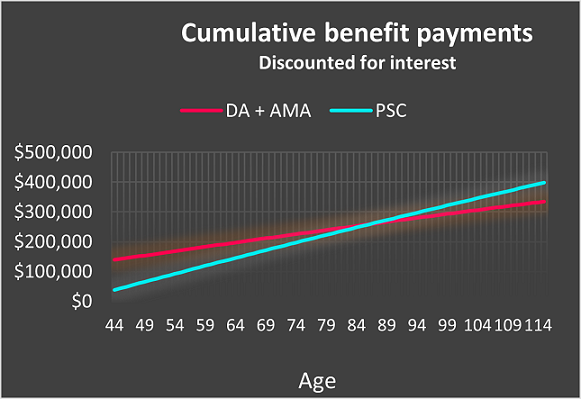

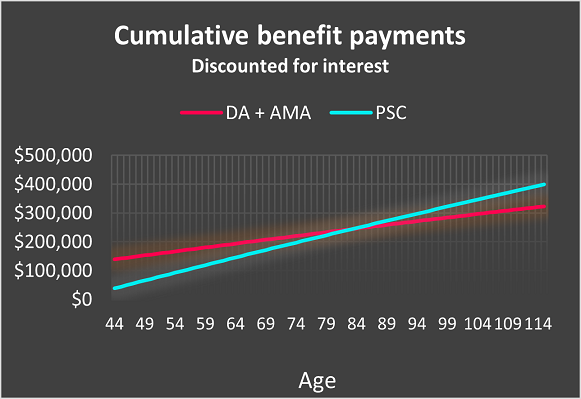

The graphs below show the two revenue streams (DA+AMA and PSC) for the VAC scenario of a female and male Veteran with a 40% DA receiving the AMA. The intersection of the two lines is the crossover point, where the present value of the two benefits is equal. It also shows the financial disparity between the AMA and the PSC recipients after the crossover point.

Anna (Female, Age 44) – 40% Disability Award on 1 April 2012

Table 1 – The crossover point is where the lines on the graph intersect – 86 years |

Additional Monthly Amount Monthly – $250 Actuarial present value summary (projected, as of 1 April 2019) DA + 136,213 Age when discounted PSC becomes greater than DA+AMA: 86 |

Alternative textA line graph shows the value of the DA plus AMA compared to the PSC over time for female Veterans. The two lines intersect at 86 years old, which is the crossover point. The graph shows that, once a female Veteran reaches the crossover point, the PSC becomes more financially valuable than the DA plus AMA. |

|

Hasan (Male, Age 44) – 40% Disability Award on 1 April 2012

Table 2 – The crossover point is where the lines on the graph intersect – 83 years[21] |

Additional Monthly Amount Monthly – $235 Actuarial present value summary (projected, as of 1 April 2019) DA + 136,213 Age when discounted PSC becomes greater than DA+AMA: 83 |

Alternative textA line graph shows the value of the DA plus AMA compared to the PSC over time for male Veterans. The two lines intersect at 83 years old, which is the crossover point. The graph shows that, once a male Veteran reaches the crossover point, the PSC becomes more financially valuable than the DA plus AMA. |

|

The failure to increase the AMA to the PSC amount at the crossover point results in an unfair outcome for elderly Veterans. As of 31 March 2021, there were 45,870 AMA recipients (Annex E, Table 1), who could eventually benefit from an increased AMA. The compensation gap between the PSC and AMA increases each month that passes following the crossover point, resulting in increasing unfairness as those recipient Veterans age.

AMA amounts by sex

VAC’s use of a male/female annuity factor in the calculation results in different AMA amounts for male and female recipients. This is because women statistically live longer than men; therefore, they have a theoretically longer offset period. According to VAC, this follows the Canadian Institute of Actuaries (Standards and Practices Manual) which requires the use of biological sex at birth mortality amounts in determining the commuted value of a pension plan (the AMA calculation is similar to the way pension plans are calculated.[22]) For the AMA, the use of the male/female factor is consistent with standard actuarial practices. Because the AMA amount remains lower than the corresponding female amount after the theoretical offset period has ended at the crossover point, the difference in the male and female amounts is based on sex and not life expectancy.

Gender-based Analysis+ considerations for the AMA

The Gender-based Analysis+[23] (GBA+) issues surrounding the AMA primarily impact gender and age, specifically, the difference in payment amounts because of gender and the failure to adjust the AMA payment at the crossover point for Veterans who live beyond the crossover point. We examined both of those aspects of the AMA in previous sections of this report.

The process of determining eligibility and delivering the AMA benefit was well designed from a service delivery perspective. VAC reviewed all DA recipients’ files to determine eligibility prior to PFL coming into force on 1 April 2019, and then facilitated payment, once contact details (banking arrangements and/or mailing addresses) were confirmed. The AMA payments automatically commenced after PFL came into force on 1 April 2019. This was all accomplished without the need for an application from the client Veteran.

The process of automatic eligibility and delivery of the AMA benefitted the following groups that traditionally may have issues with applying for VAC benefits:

- Veterans who may have challenges applying for benefits or dealing with bureaucracy or VAC.

- Veterans with cognitive challenges who may have difficulty filling out forms or online applications.

- Veterans living in remote areas without access to a government or VAC office, or reliable internet availability.

- Veterans with historic mistrust issues because of a history of mistreatment by the government (Indigenous groups, LGBTQ2S Veteran survivors of the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) purge, survivors of Military Sexual Trauma).

There may be a concern that some members of the aforementioned groups may have had difficulty applying for or receiving a DA in the first place; however DA accessibility issues are outside the scope of this investigation.

There are also 379 Veterans (Annex E, Table 4), whom VAC deemed eligible for AMA but could not contact to commence their payment.[24] VAC officials have told the OVO that the files of these Veterans are regularly reviewed for evidence of contact. If/when contact is established, VAC will commence their AMA payments. They will also receive back payments to 1 April 2019.

Findings

Following a comprehensive review of the AMA calculation, the explanations provided by VAC, and our own comparison of the present value of the PSC and the DA+AMA at the crossover point, our analysis shows that:

- The use of a sex-specific mortality rate in the calculation, resulting in different AMA amounts for males and females, is consistent with standard actuarial practices for calculating pension values. The AMA is the only VAC benefit that is paid out to individual Veterans on this basis.

- The AMA calculation, which takes into account a theoretical offset, is not adjusted once the intended purpose of the offset has been realized at the crossover point. This is the point at which the theoretical monies sought to be recovered have been repaid.

- Veterans in receipt of AMA who die before the crossover point are financially advantaged over Veterans in receipt of the monthly PSC.

- The continued application of the lower male AMA amount than the corresponding female AMA amount after the crossover point, treats men and women differently based on sex and not life expectancy.

Conclusion

Based on the analysis in the report and the findings, the following are the conclusions of this report:

- The failure to increase the AMA payment to the same amount of the PSC at the end of the theoretical offset period (the crossover point) leads to an unfair outcome for Veterans, who live beyond the crossover point, because they will be underpaid in relation to the PSC.

- Continuing to pay male Veterans, who live beyond their expected lifespan – the crossover point – a lower Additional Monthly Amount than female Veterans would then be treatment based on sex alone, not just on the statistical differences in life expectancy. This is unfair.

Recommendation

Based on the OVO’s analysis and conclusions above, the OVO recommends:

That the Minister correct the financial unfairness between the two benefits at the crossover point. Increasing the Additional Monthly Amount payment to the same rate as the Pain and Suffering Compensation payment for Veterans who live beyond their crossover point would be one way of achieving this.

Annexes

Annex A – Definitions

Annex B – Office of Veterans Ombud fairness definitions

Annex C – Background and investigation

Annex D – Pain and Suffering Compensation rate table

Annex E – Additional Monthly Amount client statistics

Annex A – Definitions

Actuarial net present value – The difference between present value cash inflows and present value cash outflows discounted for interest and probability of survival. It is used in determining the value of pensions and annuities.

Crossover point – The age when the discounted Pain and Suffering Compensation (PSC) becomes greater than the Disability Award + Additional Monthly Amount (DA+AMA). This is also the point where the monies (DA) for which the theoretical offset period was created have been repaid.[25] For Veterans born after 1956, this is 83 and 86 years of age for males and females respectively.

Clients not in pay – Those VAC clients that VAC deemed eligible for AMA on 1 April 2019, but could not be located to commence payment of their AMA.

Disability Award (DA) – A financial benefit paid to a member or a Veteran who establishes that they are suffering from a disability resulting from (a) a service-related injury or disease; or (b) a non-service-related injury or disease that was aggravated by service. The DA was paid as a lump sum, or it could be divided into a series of equal payments.[26]

Future value of money (FV)[27] – The total value of a current asset at a future date. This amount is based on an assumed rate of growth. The future value (FV) is important to investors and financial planners as they use it to estimate how much an investment made today will be worth in the future.

Life expectancy[28] – The number of years that one is expected to live as determined by statistics.

Monthly offset amount – The monthly amount that is recouped from a Veteran’s AMA monthly payment for the duration of their entire lives. An annuity factor, which takes into consideration individual circumstances to calculate any offsets to monthly payment, is used to determine this amount. This is for Veterans who are in receipt of AMA only.

Mortality rate[29] – An age- and sex-specific measure of the frequency of death occurrence within a defined population during a specified time period.

Net present value of money (NPV)[30] – The difference between present value cash inflows and present value cash outflows discounted for interest. It is used in capital budgeting and investment planning to analyze profitability of a projected investment.

Pain and Suffering Compensation (PSC) – A financial benefit paid to a member or a Veteran who establishes that they are suffering from a disability resulting from (a) a service-related injury or disease or (b) a non-service-related injury or disease that was aggravated by service.[31] The PSC can be taken as a lump-sum or as a monthly payment for life. The PSC replaced the DA on 1 April 2019, with the implementation of the Pension for Life family of benefits.

Total offset amount – The total amount to be recouped over the Veteran’s lifetime (for Veterans who are in receipt of DA+AMA only).

Annex B – Office of Veterans Ombudsman fairness definitions

Fair Process - How was it decided?

It includes an unbiased decision maker; notice of intent to make a decision; informing the Veteran of the decision-making criteria; an opportunity for the Veteran to provide evidence; timely decisions; and meaningful reasons for the decision.

Fair Treatment – How was the Veteran or family member treated?

It includes being honest and forthright when communicating and providing clear, easy-to-understand information; respecting privacy rights; and treating Veterans with courtesy, dignity and respect.

Fair Outcome – What was decided?

The decision is based on relevant information; and made in accordance with applicable laws, regulations and rules that are fair. The decision should result in equitable outcomes and not be unduly oppressive. Similarly situated individuals should expect similar outcomes.

Annex C – Background and investigation

Pain and Suffering Compensation replacing the Disability Award

On 1 April 2019, VAC implemented the PFL family of benefits. In PFL, the PSC benefit replaced the DA. The DA and the PSC are both financial compensation for a disability, and the amount is based on the percentage of disability—regardless of sex (see Annex D for PSC rate table).[32] The AMA is a separate transition benefit that was implemented for eligible DA recipients alongside the PFL family of benefits.[33]

Why was the Additional Monthly Amount developed?

The AMA benefit takes an already paid lump sum and converts it to a monthly payment to make the gap between the PSC and the DA+AMA as small as possible.[34] The intent of the AMA, as described to the VAC Minister’s Mental Health Advisory Group and the VAC Minister’s Advisory Group on Families during their respective meetings on 30 April 2019, was “…the Additional Monthly Amount was an adjustment for those who received a disability award and is not part of the PFL benefits. The intent of the Additional Monthly Amount was to ensure that those Veterans who had received a disability award would not receive less [than the PSC].[35] [36]” The AMA policy intent, which differs from the VAC statements, is stated below:

“The policy intent of the AMA is to provide a monthly payment to members and Veterans who were previously paid a Disability Award, but would have received a higher amount under the new Pain and Suffering Compensation (PSC) benefits program, if it existed prior to 1 April 2019, when they received their Disability Award.”[37]

Additional Monthly Amount – Calculation

The calculation of the AMA converts the DA already received into an amount equivalent to the monthly PSC payment, with a theoretical offset adjustment to account for the original lump-sum DA payment. The AMA is not payable if the DA paid was more than what the member or Veteran would have received under the PSC. VAC automatically calculated the payment amount if a member or Veteran was eligible to receive an AMA. There was no application process for the AMA, and there are no appeal rights in legislation. As of 31 March 2021, there were 45,870 AMA recipients – 39,473 male and 6,397 female (Annex E, Table 1).

The AMA calculation is complex, and each AMA payment is unique to the Veteran’s particular circumstance (date of birth, sex, DA(s) and date(s) received, amount of DA top-up from 1 April 2017). The scenario used below shows how the AMA is calculated and compares the AMA calculation of a female Veteran (Anna) and a male Veteran (Hasan).

Scenario—Male and female Veteran both receiving 40% disability

In 2012, Anna and Hasan (both age 44) each received a 40% DA of $119,440.[38] On 1 April 2017, they each received a one-time increase of $16,770,[39] resulting in a total payment of $136,210 each. With the implementation of PFL, they are now eligible for the AMA benefit, which entitles them to a monthly payment for life. Under PFL’s PSC at 40% disability, Anna and Hasan PSC equivalent would have been $460 per month tax free.

Formula for AMA: A – [(B – C)/D]

Where:

A – is the PSC amount that corresponds to the client’s disability percentage

B – is the sum of the following amounts:

(a) the amount of the DA paid

(b) the amount of the 1 April 2017 one-time retroactive payment due to the DA increase on 1 April 2017

C – is the product obtained by multiplying the amount determined in accordance with paragraph (a) by the number determined in accordance with paragraph (b):

(a) the PSC Amount (1 April 2019 rate) that corresponds to the client’s disability percentage

(b) the number of months included in the period beginning with the month in which the DA was paid and ending with the month of March 2019

D – is a number determined in accordance with the regulations (annuity factor)

Calculation steps: (using the scenario)

- Since they received their DA payment in 2012 (72 months ago), if it was the PFL, they would have received $33,120 in monthly PFL payments:

$460/month PFL x 72 months = $33,120

- Monthly payments from PFL ($33,120) are subtracted from the total DA they received ($136,210), which gives the amount they received above and beyond the monthly payments of $103,090. This will be recovered over the lifetime of the AMA recipient.

$136,210 - $33,120 = $103,090

- The $103,090 will be spread over the rest of Anna and Hasan’s lives by calculating a monthly offset. This is to minimize the impact on their additional monthly payment, to ensure it is as close as possible to what the payment would have been under PFL.

Anna: $103,090 / annuity factor = $210/month

Hasan: $103,090 / annuity factor = $230/month

- The annuity factor considers male and female mortality rates, inflation, and interest rates. Anna’s amount is different because women are generally projected to live longer lives than men. The DA that both Veterans received is then factored in.

Anna AMA: $460 (PFL Amount) - $210 (Monthly Offset) = $250/month for life

Hasan AMA: $460 (PFL Amount) - $230 (Monthly Offset) = $230/month for life

As of 1 April 2019, Anna will receive $250/month and Hasan will receive $230/month tax free for life. This is in addition to the $136,210 they have already received from their DA.

Comparing the DA+AMA to the PSC

The OVO hired an independent actuary to build a computer model to compare the lifetime value of the DA+AMA to the PSC.[40] The model calculates AMA and PSC future revenue using the following variables: age, sex, DA(s) awarded for % disabled and date(s) awarded. The present value of each revenue stream is then compared for the given scenario (see Annex A – Definitions), to determine where the revenue streams intersect. The model also determines the age, if the Veteran were to survive, at which the cumulative PSC revenue becomes greater than the DA+AMA (henceforth called the crossover point).[41] The model does not predict the lifespan of the recipient. Because the AMA period of offset never ends, both the AMA and PSC remain unchanged throughout the life of the recipient.[42]

According to the OVO model, the crossover point for men and women, born in 1956 or later, is 83 and 86 years of age respectively.[43] [44] In VAC’s example of Hasan and Anna, if or when Hasan reaches 83 and Anna reaches 86 years old, they will continue to receive their AMA of $230 and $250 respectively each month for life, while the PSC recipients will continue with $460/month for life. In other words, from the crossover point, Hasan will receive $230 less and Anna $210 less, each month, than their PSC counterparts (See Tables 1 and 2 below).

Anna (Female, Age 44) – 40% Disability Award on 1 April 2012

Table 1 – The crossover point is where the lines on the graph intersect – 86 years |

Additional Monthly Amount Monthly – $250 Actuarial present value summary (projected, as of 1 April 2019) DA + 136,213 PSC 259,233 Age when discounted PSC becomes greater than DA+AMA: 86 |

Alternative textA line graph shows the value of the DA plus AMA compared to the PSC over time for female Veterans. The two lines intersect at 86 years old, which is the crossover point. The graph shows that, once a female Veteran reaches the crossover point, the PSC becomes more financially valuable than the DA plus AMA. |

|

Hasan (Male, Age 44) – 40% Disability Award on 1 April 2012

Table 2 – The crossover point is where the lines on the graph intersect – 83 years[45] |

Additional Monthly Amount Monthly – $235 Actuarial present value summary (projected, as of 1 April 2019) DA + 136,213 PSC 244,151 Age when discounted PSC becomes greater than DA+AMA: 83 |

Alternative textA line graph shows the value of the DA plus AMA compared to the PSC over time for male Veterans. The two lines intersect at 83 years old, which is the crossover point. The graph shows that, once a male Veteran reaches the crossover point, the PSC becomes more financially valuable than the DA plus AMA. |

|

|

Note: The OVO model shows Hasan’s AMA amount as $235/month, while the VAC example calculates it to be $230/month. The discrepancy is explained by the precision of the OVO model. The model is accurate according to the tables and assumptions used by the Office of the Chief Actuary (OCA), when they developed the AMA calculation. The VAC example was created for illustrative purposes before OCA finalized the AMA inputs. The OVO model is accurate in accordance with scenarios provided by OCA and real-life examples obtained by OVO. |

Why is a female’s AMA amount higher than a male’s?

The female’s AMA amount is higher than a male’s because of the way it is calculated. On average, women have a longer expected lifespan than men do, which is reflected in a sex-specific mortality rate,[46] resulting in different AMA amounts.

Once the offset amount is determined, VAC uses an annuity factor to determine the amount of theoretical collection of the offset over their expected lifespans while still allowing for an AMA payment. The annuity factor includes a sex-specific mortality rate[47] that accounts for a women’s longer expected lifespan compared to a man’s expected lifespan.

Because Anna’s expected lifespan is longer, she will have a longer theoretical offset period to repay the difference between the DA and the monthly PSC (up to 1 April 2019). Therefore, her offset amount will be lower than Hasan’s. Anna’s monthly offset is $210 per month for the rest of her life while Hasan’s is $230 per month for the rest of his life. Subtracted from the $460/month PSC they would have received up to 31 March 2019 if PSC was available, Anna’s AMA will be $250/month and Hasan’s will be $230/month.

Annex D – Pain and Suffering Compensation rate table

Effective date as of 1 April 2019[48]

|

Rate of Pain and Suffering Compensation (%) |

Extent of disability (%) |

PSC monthly amount ($) |

PSC lump-sum amount ($) |

|

100 |

98-100 |

1150.00 |

365,400.00 |

|

95 |

93-97 |

1092.50 |

347,130.00 |

|

90 |

88-92 |

1035.00 |

328,860.00 |

|

85 |

83-87 |

977.50 |

310,590.00 |

|

80 |

78-82 |

920.00 |

292,320.00 |

|

75 |

73-77 |

862.50 |

274,050.00 |

|

70 |

68-72 |

805.00 |

255,780.00 |

|

65 |

63-67 |

747.50 |

237,510.00 |

|

60 |

58-62 |

690.00 |

219,240.00 |

|

55 |

53-57 |

632.50 |

200,970.00 |

|

50 |

48-52 |

575.00 |

182,700.00 |

|

45 |

43-47 |

517.50 |

164,430.00 |

|

40 |

38-42 |

460.00 |

146,160.00 |

|

35 |

33-37 |

402.50 |

127,890.00 |

|

30 |

28-32 |

345.00 |

109,620.00 |

|

25 |

23-27 |

287.50 |

91,350.00 |

|

20 |

18-22 |

230.00 |

73,080.00 |

|

15 |

13-17 |

172.50 |

54,810.00 |

|

10 |

8-12 |

115.00 |

36,540.00 |

|

5 |

5-7 |

57.50 |

18,270.00 |

|

4 |

4 |

46.00 |

14,616.00 |

|

3 |

3 |

34.50 |

10,962.00 |

|

2 |

2 |

23.00 |

7,308.00 |

|

1 |

1 |

11.50 |

3,654.00 |

Annex E – Additional Monthly Amount client statistics

Table 1 – AMA clients as of 31 March 2021, by age

|

Age |

Number of clients |

|

29 and under |

1,181 |

|

30 to 39 |

8,453 |

|

40 to 49 |

10,674 |

|

50 to 59 |

16,575 |

|

60 to 69 |

7,160 |

|

70 to 79 |

1,803 |

|

80 to 90 |

24 |

|

Total |

45,870 |

Table 2 – AMA clients as of 31 March 2021 by sex

|

Sex |

Number of clients |

Percentage (%) |

|

Male |

39,473 |

86 |

|

Female |

6,397 |

14 |

|

Total |

45,870 |

100 |

Table 3 – AMA clients as of 31 March 2021 by age and sex

|

Age |

Female |

Male |

Total |

|

29 and under |

191 |

990 |

1,180 |

|

30 to 39 |

1,133 |

7,320 |

8,453 |

|

40 to 49 |

1,767 |

8,970 |

10,674 |

|

50 to 59 |

2,387 |

14,188 |

16,575 |

|

60 to 69 |

874 |

6,286 |

7,160 |

|

70 to 79 |

43 |

1,760 |

1,803 |

|

80 to 90 |

2 |

22 |

24 |

|

Total |

6,397 |

39,473 |

45,870 |

Table 4 – AMA eligible clients as of April 2021, but not in pay[49]

|

Age |

Female |

Male |

Total |

|

20-29 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

30-39 |

13 |

68 |

81 |

|

40-49 |

6 |

41 |

47 |

|

50-59 |

6 |

65 |

71 |

|

60-69 |

2 |

49 |

51 |

|

70-79 |

2 |

41 |

43 |

|

80-89 |

3 |

67 |

70 |

|

90-99 |

0 |

13 |

13 |

|

Total |

33 |

346 |

379 |

References

- Billing, A. (2018, December, 31). Actuarial Report (30th) on the Canada Pension Plan. Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, Department of Finance, Government of Canada. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from: https://www.osfi-bsif.gc.ca/Eng/oca-bac/ar-ra/cpp-rpc/Pages/cpp30.aspx#TOC-1

- Canadian Institute of Actuaries. (2020, December 1). Standards and Practice - Pension Plans (Part 3000). Retrieved February 28, 2021, from: https://www.cia-ica.ca/docs/default-source/standards/sp120120e.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012, May 18). Principles of Epidemiology in Public Health Practice - Lesson 3 Measures of Risk. (C. F. Deputy Director for Public Health Science and Surveillance, Ed.). Retrieved March 2, 2021, from: https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson3/section3.html#:~:text=A mortality rate is a measure of the, what you choose to measure illness or death

- Chen, J. (2020, October 22). Tools for Fundamental Analysis - Future Value (FV). Investopedia. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/futurevalue.asp#:~:text=Future value %28FV%29 is the value of a, can be

- Dictionary.com. (2002, 2001, 1995). Life expectancy. Houghton Mifflin Company. Retrieved March 2, 2020, from: https://www.dictionary.com/browse/life-expectancy

- Employment and Social Development. (2020, April 27). CPP Retirement Pension: Overview. Government of Canada. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/publicpensions/cpp.html

- Fernando, J. (2021, March 1). Net Present Value (NPV). (J. Mansa, Ed.). Investopedia. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/n/npv.asp#:~:text=Net present value %28NPV%29 is a financial metric,the present day%2C and then add them together

- Justice Laws Website. (2019, April 1). Veterans Well-being Regulations (SOR/2006-50). Retrieved March 2, 2021, from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/SOR-2006-50/index.html

- Justice Laws Website. (2020, July 27). Veterans Well-being Act (S.C. 2005, c.21). Retrieved March 2, 2021, from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-16.8/

- Justice Laws Website. (2021, February 24). Access to Information Act. Retrieved March 11, 2021, from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/A-1/page-6.html#h-550

- Office of the Veterans Ombudsman. (2021, January 15). Financial Compensation for Canadian Veterans - A Comparative Analysis of Benefit Regimes. Government of Canada. Retrieved April 5, 2021, from: https://ombudsman-veterans.gc.ca/en/publications/reports-reviews/financial-compensation-analysis#anna

- Rischatsch Dr, M., Pain, D., Ryan, D., & Chiu, Y. (2018, October 15). Mortality improvement: Understanding the Past and Framing the Future. (B. Rogers Dr, Ed.). (Swiss Re Institute - Sigma No 6/2018.). Retrieved March 2, 2021, from: https://www.swissre.com/dam/jcr:81871581-01f0-450a-adec-37cc5f6534e0/sigma6_2018_en.pdf

- Statistics Canada. (2015-2019). Table 13-10-0392-01 Deaths and age-specific mortality rates, by selected grouped causes. Government of Canada. Retrieved from: https://www.doi.org/10.25318/1310039201-eng

- Status of Women Canada. (2020, October 28). Gender-based Analysis Plus. Government of Canada. Retrieved March 24, 2021, from: https://cfc-swc.gc.ca/gba-acs/index-en.html

- Veterans Affairs Canada, AMA Policy Statement. (2019, April 1). Additional Monthly Amount Policy. (P. a. Director General, Ed.). Government of Canada. Retrieved March 2, 2021, from: intranet.vac-acc.gc.ca/eng/operations/vs-toolbox/policies/policy/2827

- Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019, February 19). Disability Award Increase FAQ page. Government of Canada. Retrieved March 4, 2021, from: https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/help/faq/disability-award-increase#a03

- Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019, April 1). How The Additional Monthly Payment is Calculated. Government of Canada. Retrieved March 02, 2021, from: https://indd.adobe.com/view/c785eccf-a9e1-4429-8adf-1c7032a3c73e

- Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019, April 1). Pain and Suffering Compensation Policy. Government of Canada. Retrieved April 2, 2021, from: intranet.vac-acc.gc.ca/eng/operations/vs-toolbox/policies/policy/2826

- Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019, November 4). Record of Discussion – Mental Health Advisory Group Meeting April 30, 2019. Government of Canada. Retrieved May 5, 2021, from: https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/about-vac/what-we-do/public-engagement/advisory-groups/mental-health-advisory-group/04-30-2019

- Veterans Affairs Canada. (2020, September 30). Pension for Life - Questions and Answers. Government of Canada. Retrieved from: https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/services/pension-for-life/q-and-a#a9

Acknowledgements

Lead Investigator

Jamie Morse

Researcher

Michelle Golub

Directing Managers

Sharon Squire - Deputy Ombud

Duane Schippers - Director of Strategic Review and Analysis

Footnotes

[1] These calculations use statistics and financial theory to compare a lump sum (DA) to monthly payments (AMA and PSC) in present-day dollars. They are usually done by a financial risk specialist, or actuary.

[2] See Annex A - Definitions

[3] Pain and Suffering Compensation (PSC) is a financial benefit paid “…to a member or a Veteran who establishes that they are suffering from a disability resulting from (a) a service-related injury or disease; or (b) a non-service-related injury or disease that was aggravated by service.” Justice Laws Website. (2020). Well-being Act, Part 3 para 45(1) (a) and (b). Retrieved from https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-16.8/

[4] For the purposes of this investigation, when the term Veteran(s) is used in relation to the AMA, it also includes serving Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members receiving or eligible for the AMA.

[5] Disability Award (DA) is a financial benefit paid to “…a member or a Veteran who establishes that they are suffering from a disability resulting from (a) a service-related injury or disease; or (b) a non-service-related injury or disease that was aggravated by service.” Justice Laws Website. (2019). Veterans Well-being Act, Part 3 para 45(1) (a) and (b). Retrieved from laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-16.8/20180401/P1TT3xt3.html

[6] Information source: March 2021 VAC Client Files. Prepared by VAC Statistics Directorate, July, 2021.

[7] The model uses the same data used by VAC to calculate the future value of the revenue streams of the two benefits so they can be fairly compared.

[8] The theoretical offset can also be considered as a credit of amount received over and above any PSC payments that would have been paid. In this investigation, we will use the term offset, meaning theoretical offset, to remain consistent with the VAC online AMA calculation examples. When referring to repaying the offset, this is also a theoretical repayment, as no monies are actually collected.

[9] Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019). How the Additional Monthly Payment is Calculated. Retrieved from indd.adobe.com/view/c785eccf-a9e1-4429-8adf-1c7032a3c73e

[10] DA recipients had the option of having their award paid in one lump-sum payment or spread over a number of annual payments. This is not comparable to the PSC monthly payments for life.

[11] The 1 April 2019 PSC rate table is used because all AMA calculations are based on 1 April 2019.

[12] It is a normal actuarial practice to convert a monthly payment or annuity into a lump sum (e.g., payout of an annuity), but it is less common to convert a lump sum into a monthly payment—especially when that lump sum was already paid and has to be recovered.

[13] Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019). Additional Monthly Amount Policy. Retrieved from intranet.vac-acc.gc.ca/eng/operations/vs-toolbox/policies/policy/2827

[14] Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019). Record of Discussion—Mental Health Advisory Group: Retrieved from Record of Discussion – April 30, 2019 – Mental Health Advisory Group – Veterans Affairs Canada

[15] Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019). Record of Discussion – Advisory Group on Families. Retrieved from Record of Discussion – April 30, 2019 – Veterans Affairs Canada

[16] Statistics Canada. (2020). Retrieved from Table 13-10-0392-01 Deaths and age-specific mortality rates, by selected grouped causes

[17] Note: Veterans born before 1956 could have a later crossover point depending on their birth date, the date they received their DA(s) and the size of their DA(s).

[18] The model does not predict the lifespan of the Veteran. It shows the age [for the AMA recipient] at which the value of the DA+AMA and monthly PSC benefit intersect.

[19] Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019). Record of Discussion – Mental Health Advisory Group. Retrieved from Record of Discussion – April 30, 2019 – Veterans Affairs Canada

[20] Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019). Record of Discussion – Care and Support Advisory Group. Retrieved from Record of Discussion – April 30, 2019 – Veterans Affairs Canada

[21] The OVO model shows Hasan’s AMA amount as $235/month, while the VAC example calculates it to be $230/month. The discrepancy is explained by the precision in the OVO model (see Annex C for more detailed explanation).

[22] Canadian Institute of Actuaries. (2018) Standards and Practices Manual (page 3046, Section 3530.01). Retrieved from Standards of Practice: Part 3000 – Pensions (cia-ica.ca). This section states that separate mortality rate amounts for male and female members are assumed when calculating the commuted value of a pension plan. This calculation is consistent with standard actuarial practices of the Canadian Institute of Actuaries and Public Service Accounting Standards for reporting in public accounts and is commonly used to calculate amounts when turning a lump-sum payment into an annuity.

[23] “Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) is an analytical process used to assess how diverse groups of women, men, and gender diverse people may experience policies, programs and initiatives. The “plus” in GBA+ is not just about differences between biological (sexes) and socio-cultural (genders). It also considers many other identity factors such as race, ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability and how the interaction between these factors influences the way we might experience government policies and initiatives.” Government of Canada. (2020). What is Gender-based Analysis Plus. Retrieved from https://femmes-egalite-genres.canada.ca/en/gender-based-analysis-plus/what-gender-based-analysis-plus.html

[24] VAC told OVO that at the time of implementation of the AMA, they sent two letters to the addresses they had on file, communicated through the VAC website and social media, and consulted with stakeholder to contact the outstanding AMA eligible Veterans. The 379 files are manually reviewed periodically to determine if contact has been made with VAC. There are multiple client notes on these Veterans’ accounts advising the NCCN and area offices that if these Veterans contact VAC, a work item is to be sent to Benefits Processing Pay so they may initiate payment of AMA and back pay.

[25] Crossover point is the term used by OVO for this investigation only.

[26] Justice Laws Website. (2019). Veterans Well-being Act, Part 3 para 45(1) (a) and (b). Retrieved from laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-16.8/20180401/P1TT3xt3.html

[27] Investopedia.com. (n.d.). Future Value (FV). Retrieved from investopedia.com/terms/f/futurevalue.asp#:~:text=Future value %28FV%29 is the value of a, can be

[28] Dictionary.com. (n.d.). Life expectancy. Retrieved from Definition of Life expectancy at Dictionary.com

[29] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Lesson 3: Measures of Risk. Retrieved from cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson3/section3.html#:~:text=A mortality rate is a measure of the, what you choose to measure%2C illness or death

[30] Investopedia.com. (n.d.) Net Present Value (NPV). Retrieved from investopedia.com/terms/n/npv.asp#:~:text=Net present value %28NPV%29 is a financial metr ic, the present day%2C and then add them together.

[31] Justice Laws Website. (2019). Veterans Well-being Act, Part 3 para 45(1) (a) and (b). Retrieved from laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-16.8/20180401/P1TT3xt3.html

[32] The 1 April 2019 PSC rate table is used because all AMA calculations are based on 1 April 2019.

[33] The Office of the Veterans Ombudsman’s Financial Compensation for Canadian Veterans – A Comparative Analysis of Benefit Regimes report conducted an actuarial analysis of the PFL benefits to compare them to Veterans Well-being Act and Pension Act. The AMA was not included in this comparison. Office of the Veterans Ombudsman. (2021). Financial Compensation for Canadian Veterans. Retrieved from https://ombudsman-veterans.gc.ca/en/publications/reports-reviews/financial-compensation-analysis#anna

[34] It is a normal actuarial practice to convert a monthly payment (annuity) into a lump sum (e.g., payout of an annuity), but it is less common to convert a lump sum into a monthly payment—especially when that lump sum was already paid, and has to be recovered.

[35] Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019). Record of Discussion – Mental Health Advisory Group. Retrieved from Record of Discussion – April 30, 2019 – Veterans Affairs Canada

[36] Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019). Record of Discussion – Care and Support Advisory Group. Retrieved from Record of Discussion – April 30, 2019 – Veterans Affairs Canada

[37] Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019). Additional Monthly Amount Policy. Retrieved from intranet.vac-acc.gc.ca/eng/operations/vs-toolbox/policies/policy/2827

[38] Veterans Affairs Canada. (2019). Pension for Life Website – Already Received a Disability Award? 40% scenario. Retrieved from https://indd.adobe.com/view/c785eccf-a9e1-4429-8adf-1c7032a3c73e

[39] As of 1 April 2017, the maximum DA amount (for 98% to 100% disability) increased to $360,000. All other DA amounts (1% to 97%) were also increased proportionally as a percentage of the maximum $360,000 amount. Anyone who received a DA prior to 1 April 2017 was eligible to receive a one-time retroactive payment.

[40] The model was constructed using the same mortality tables and assumptions used by the Office of the Chief Actuary (OCA) used in the development of the AMA.

[41] Crossover point is the unofficial OVO term used to represent the age when the discounted PSC becomes greater than the DA+AMA. It is also the point where the amount of the DA for which the (theoretical) offset period was created has been repaid.

[42]AMA and PSC are both adjusted annually for cost of living and interest rate.

[43] The crossover points of 83 and 86 years for men and women respectively is consistent for Veterans born in 1956 and later who are eligible for the AMA, regardless of age at which the award was issued or percentage of disability. For Veterans born earlier than 1956, the actuarial concept of conditional life expectancy affects the crossover point. The closer they are to their life expectancy, the more probable it is they will live longer than their projected life expectancy. This means if they are eligible for the AMA, their crossover point would increase in age.

[44] Approximately 88% of AMA recipients were born in 1956 or later (Annex E, Table 1).

[45] The OVO model shows Hasan’s AMA amount as $235/month, while the VAC example calculates it to be $230/month. The discrepancy is explained by precision in the OVO model (see Annex C for more detailed explanation).

[46] The annuity factor includes three components: (1) gendered-life-expectancy rates, (2) interest rates (3) cost-of-living adjustments.

[47] The annuity calculation was developed by the Office of the Chief Actuary (OCA) and incorporates inflation rates, interest rates, and gender-specific Veteran mortality amounts.

[48] Government of Canada. (2019). Veterans Well-being Act. Retrieved from https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-16.8/20190401/P1TT3xt3.html

[49] Clients not in pay are those VAC clients that VAC deemed eligible for AMA on 1 April 2019 but could not be located. They were sent two letters to their last known address, contact was attempted through My VAC Account, in cases when accounts existed, and there was an extensive advertisement and social media campaign to contact them. Their files are noted and regularly reviewed. They will be eligible for their AMA back to 1 April 2019 when they can next be contacted (information provided by VAC AMA Program Area, 29 April 2021).