Table of Contents

Message from the Ombudsman

I am pleased to publish the research findings for Transitioning Successfully: A Qualitative Study. Based on the lived experiences of medically-released Veterans who self-identified as having successfully transitioned, this study highlights some of the factors that contribute to a successful transition as well as the challenges that Veterans and their families face during the transition to civilian life.

This report examines the factors that contribute to a successful transition for medically-released Veterans in two phases – a literature review and a qualitative research study involving in-depth interviews with Veterans. The stories of the Veterans interviewed are shared throughout the report and reflect the insight and experiences of those who have successfully navigated the transition process.

There is little research that examines the determinants of successful transition of medically-released Canadian Veterans, and as a result, I hope that the results of this study will inform other Canadian research efforts. It will also serve as a basis for the Office of the Veterans Ombudsman’s future work on transition.

I hope that those about to transition, or currently in transition from military to civilian life, as well as decision makers with the power to improve the transition process, will find the findings and personal stories insightful.

Guy Parent

Veterans Ombudsman

Executive Summary

To better understand the factors that contribute to a successful transition from military to civilian life, the Office of the Veterans Ombudsman (OVO) initiated a two-phased study to explore the lived experience of Veterans and learn about:

- the factors which contribute to a successful transition;

- the programs and services which facilitated a successful transition; and

- the challenges they faced during the transition process.

Phase I – Literature Review

Through a contract with the Canadian Institute of Military Veterans Health Research (CIMVHR), a literature reviewFootnote 1 was completed to identify a comprehensive list of factors that contribute to a successful transition to civilian life for medically-released Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) Veterans. The results of this review were presented at the 2015 CIMVHR Forum.

The literature review suggests that the most important determinants of successful transition in general were related to finding satisfying work, mental health, and the relationship with the spouse and family. However, it is important to note that while large scale research initiatives are currently underway by the CAF and Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) to better understand military to civilian transition, there is a dearth of independent research available on the transition experiences of Canadian Veterans, and less still that is related specifically to the medically-released population. There is also a scarcity of articles related to identifying the factors in facilitating a successful transition for medically-released Canadian Veterans, and there is no widely accepted definition of a successful transition from military to civilian life.

The literature review highlighted the need for more independent research on the transition experiences of Canadian Veterans and on the post-2006 medically-released Veteran population to better understand the effects of the New Veterans Charter (NVC) on successful transition outcomes.

Phase II – Qualitative Study

This phaseFootnote 2 explored the transition process, based on the lived experiences of 15 Veterans who were medically-released between 2006 and 2014, and who self-identified as having successfully transitioned. Each participant completed an online survey followed by an in-depth telephone interview. The in-depth interview, informed by the results of the literature review and the online survey, probed the lived experiences of the participants. All online surveys were completed between the end of October and the end of November 2016. The telephone interviews began in early November and finished in early December 2016 and were conducted by EKOS Research Associates.

The results from the survey and subsequent interview provided invaluable insight into the unique experiences of participants. Interestingly, many noted that there was no specific time or event at which point they considered their transition “complete”. Rather, they eventually began to accept the adjustment to civilian life.

Phase II – Qualitative Study

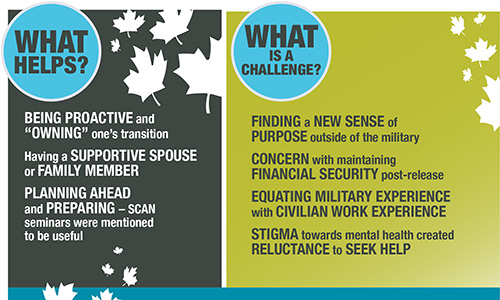

What Helps?

- Being proactive and "owning" one's transition

- Having a supportive spouse or family member

- Planning ahead and preparing - SCAN seminars were mentioned to be useful

What is a challenge?

- Finding a new sens of purpose outside of the military

- Concern with maintaining financial security post-release

- Equating military experience with civilian work experience

- Stigma towards mental health created reluctance to seek help

The survey resultsFootnote 3 and follow-up interviews with Veterans identified the following contributors to successFootnote 4:

- Being proactive and “owning” their transition;

- Support from a spouse; and

- Planning ahead for the transition.

The most challenging elements reported were:

- Finding a new sense of purpose outside of the military, including finding a new or different way to serve and be of value to their community;

- Stress over financial security; and

- Stigma around seeking treatment for injuries, particularly mental health injuries.

Conclusion

This study into the lived experience of successful transition for medically-released Canadian Veterans provides information that will help improve processes, programs, and services. The findings identified key contributors and challenges consistent with the findings from the Phase I literature review. While the literature review looked at a broader group of transitioning Veterans, the importance of finding new purpose after release, including family members in the transition process, and realizing and addressing the stigma of mental illness were all noted to be required for a successful transition. Additionally, the results of the online survey and in-depth interviews echoed the findings of the Life After Service Studies (LASS) 2016 survey conducted by VAC. Almost a third of Veterans (32%) report difficulty with their transition in the LASS survey and among our participants, nine of the 15 reported that their transition was either moderately or very difficult. The results of this study were presented at the 2017 CIMVHR Forum. As the first qualitative research study of medically-released Canadian Veterans, it will hopefully inform other research into Canadian Veterans and will provide the foundation for the OVO’s future research on transition including, potentially, a focus group with family members to better understand their lived experience through the transition process.

Introduction

To better understand the factors that contribute to a successful transition from military to civilian life for Canadian medically-released Veterans, the OVO initiated a two-phased study. Through a review of peer-reviewed research and in-depth interviews with 15 medically-released Veterans who self-identified as having successfully transitioned, several contributors and challenges were identified. This report provides an overview of the determinants of successful transition and includes a summary of the literature review and the findings from the qualitative research study.

The research objectives, for both the literature review and qualitative research study were to better understand:

- the factors which contribute to a successful transition;

- programs and services which facilitate a successful transition; and

- the challenges in the transition process.

The insight into the lived experience of medically-released Veterans and the processes, programs and services that they feel most contributed to a successful transition will provide information to help improve and tailor the supports provided to medically-releasing CAF members, Veterans and their families.

Methodology

The project methodology included two phases. The first phase was a literature review contracted through CIMVHR. Based on the findings from the literature review, CIMVHR developed the research methodology for the second phase, including the participant recruitment and selection criteria, the interview guide, and the areas of interest identified in the literature review which may contribute to success.

The second phase used two research methods: an online survey and a semi-structured in-depth telephone interview. The Standards for the Conduct of Government of Canada Public Opinion Research Qualitative ResearchFootnote 5 were followed to ensure that the objectives were met and that the research undertaken conformed to the legislative and policy requirements as well as Government of Canada and industry standards.

The OVO recruited participants through stakeholders, the OVO website and social media, seeking a maximum of 20 volunteers who were Canadian Veterans medically-released between 2006 and 2014 and who self-identified as having successfully transitioned.

The OVO screened and selected 15 volunteers from the 25 respondents to achieve a small sample of participants including regular and reserve force, male and female, officer and non-officer and varied years of service (Appendix 1 – Screening Questionnaire). It is important to note that no individual was screened out as the ten Veterans not selected were deemed as having “dropped out” after not completing the full screening process (i.e. they stopped responding to emails or did not complete the screening questionnaire). The 15 participants who were selected met the OVO established screening requirements.

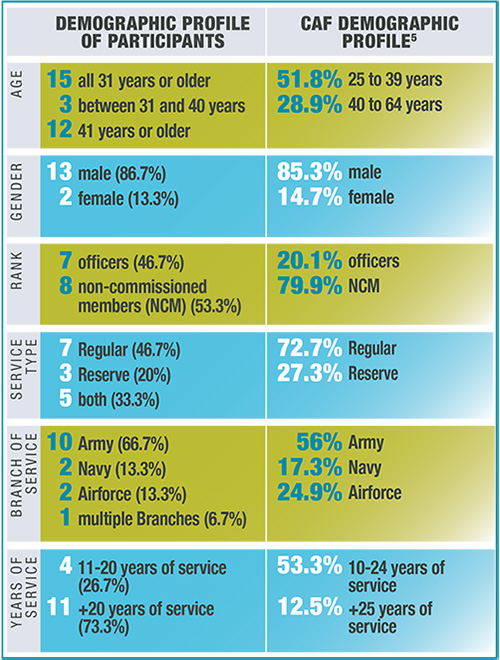

Table 1 shows the demographic breakdown of participants compared to the current CAF demographic profile:

Table 1 – Demographic Profile of ParticipantsFootnote 5

Demographic Profile of Participants

| Demographic profile of participants | CAF Demographic profileFootnote 6 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age |

|

|

| Gender |

|

|

| Rank |

|

|

| Service Type |

|

|

| Branch of service |

|

|

| Years of service |

|

|

All participants were provided with a consent form informing them that their participation was confidential and voluntary, and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. They were advised of their rights under the Privacy Act and Access to Information Act and the OVO ensured that those rights were protected throughout the research process. All selected participants completed a consent to participate form based on academic research best practices and Government of Canada Public Opinion Research standards.

The participants were then administered an online survey using the FluidSurveys online tool (Appendix 2). The survey consisted of 42 closed-ended questions, divided into seven areas of interest based on the findings from the literature review:

- Transition Process

- Transition Programs and Services

- Health and Disability

- Employment and Education

- Income and Financial Well-being

- Family, Peer Support and Social Support

- Military Culture

In addition, the survey gathered data on demographic and service related factors. The majority of questions used a Likert response scale, and the full survey took approximately 30 minutes to complete.

Once completed, the results were sent to EKOS Research Associates who then scheduled a one-on-one, in-depth telephone interview with each participant.

- The interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview approach. This allowed the interviewer to tailor each interview to the experiences of the participant while maintaining a consistent structure for each interview. The interview guide is cited in Appendix 3.

- Each interview started with broad demographic questions designed to both inform the context of the participant’s service and transition as well as ease into more sensitive topics. Broad questions were followed by probing questions if the area was relevant to the participant’s unique transition experience.

- The interview guide was pre-tested with a panel of Veterans working at the OVO who were medically-released and self-identified as having had a successful transition. This pre-testing allowed for refinement of the wording of the questions and the addition of more probing question integration into the interview guide. The results of the pre-test were saved and are not included the data gathered.

- While the interviewer used the interview guide, each interview was tailored to each participant’s personal experiences and to responses obtained from the participant in the online survey. The online survey tool helped to both reduce the length of the in-depth interview and focus the conversation.

EKOS Research Associates conducted the 15, in-depth interviews, between November 9th and December 8th, 2016 and each lasted between 45-60 minutes.

- One interview was conducted in French. At the start of each interview, participants were reminded again, that their participation was voluntary, that they could withdraw from the research at any-time, and that their participation would be kept anonymous. A thank-you letter was sent to all the participants from the Veterans Ombudsman upon completion of the interviews.

- EKOS Research Associates completed an analysis and report of findings for the in-depth interviews.Footnote 7

Findings from Phase I – Literature Review

To understand the current Canadian research on transition from military to civilian life, and to identify which factors contributed to a successful transition to civilian life for medically-released CAF Veterans, a literature review of peer-reviewed work from both academic and Government sources was completed.

The literature review considered the research question: What factors result in a successful transition to civilian life for CAF members including medically-released CAF Veterans? In total, 94 relevant studies were identified, and most looked at all Veterans without identifying medical or non-medical release. Eighteen studies addressed the determinants of successful transition and only two focused on investigating transition issues for medically-released CAF Veterans compared to their non-medically-released peers.

The literature review suggests the lack of a commonly accepted definition of a successful transition from military to civilian life in the Canadian context; however, recent research proposes the following definition of military to civilian transition (MCT):

The process through which military Veterans and their immediate family members achieve and maintain a stable level of psychological, physical and economic well-being. They are satisfied with their abilities to meet their immediate and long-term economic needs and are committed to a post-military identity and sense of purpose that allows them to engage in productive work and social connectivity commensurate with individual goals, desires and abilities Footnote 8

One of the most in-depth studies on transition facilitators was an independent online surveyFootnote 9 where Veterans were asked to report the most important contributors to a successful transition. The results by percentage of 190 respondents indicated that the most important determinants of successful transition were:

- finding satisfying work (26.8%);

- stable mental health (20%); and

- relationship with spouse (16.8%) and family (18.9%).

The same study reported that 28.4% felt that transition would be easier if Canadians understood more about the military way of life; 28.4% said, “if I had more money”; and 11.8% said, “if I had someone to talk to”.

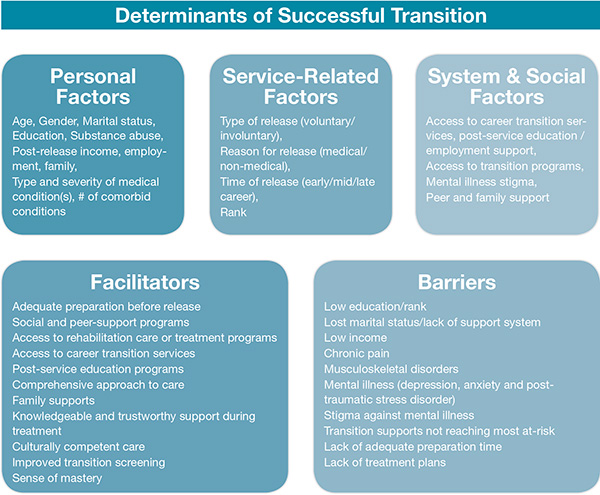

The factors identified in the research that facilitate successful transition outcomes for CAF members can be grouped into: a) personal factors, b) service related factors and c) system and social factors. Figure 1 illustrates the link between the personal, service, and system and social factors and the barriers or facilitators identified from the literature review. Figure 2 suggests possible actions to improve successful transition.

Figure 1 – Barriers and Facilitators

Barriers and Facilitators

Determinants of Successful Transition

Personal Factors

- Age, Gender, Marital status, Education, Substance abuse,

- Post-release income, employment, family,

- Type and severity of medical condition(s), # of comorbid conditions

Service-Related Factors

- Type of release (voluntary/involuntary),

- Reason for release (medical/non-medical),

- Time of release (early/mid/late career),

- Rank

System & Social Factors

- Access to career transition services, post-service education /employment support,

- Access to transition programs,

- Mental illness stigma,

- Peer and family support

Facilitators

- Adequate preparation before release

- Social and peer-support programs

- Access to rehabilitation care or treatment programs

- Access to career transition services

- Post-service education programs

- Comprehensive approach to care

- Family supports

- Knowledgeable and trustworthy support during treatment

- Culturally competent care

- Improved transition screening

- Sense of mastery

Barriers

- Low education / rank

- Lost marital status / lack of support system

- Low income

- Chronic pain

- Musculoskeletal disorders

- Mental illness (depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder)

- Stigma against mental illness

- Transition supports not reaching most at-risk

- Lack of adequate preparation time

- Lack of treatment plans

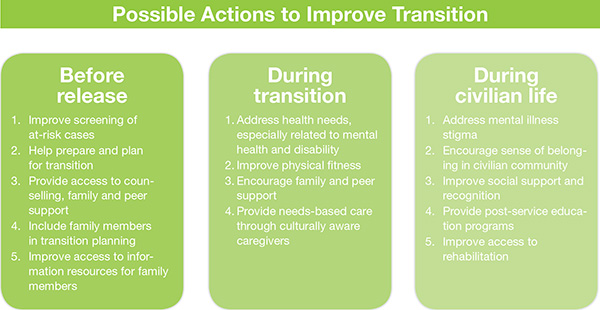

Figure 2 – Improvements to the Transition Process

Improvements to the Transition Process

| Possible Actions to Improve Transition | ||

|---|---|---|

| Before release | During transition | During civilian life |

|

|

|

The key findings of the literature review highlighted that:

- There is no established or commonly accepted definition of a successful transition from military to civilian life in the Canadian context;

- Very few Canadian studies have been conducted on the determinants of successful transition to civilian life for CAF members and there are few articles specifically dedicated to determining the most important factors that facilitate a successful transition for medically-released Veterans in Canada;

- The majority of studies have looked at all Veterans, without identifying the reason for release (medical or non-medical). The bulk are cross-sectional quantitative studies based on surveys (57%) and literature reviews (29%). Only 14% were based on qualitative methodologies; and

- The majority of surveys conducted were based on cohorts that had not experienced transition under the NVC (after 2006) or had only a small number of NVC subjects in their cohort. Given the significant policy changes implemented with the NVC, this is a compelling rationale for more Canadian research to evaluate transition outcomes.

While large scale research initiatives are currently under way by the CAF and VAC to better understand the transition from military to civilian life, there is a dearth of independent research available on the transition experiences of Canadian Veterans in general and even less research specifically on the medically-released population. As such, it is hoped that this research will help inform future priorities and research conducted by the Government of Canada as the lack of research related to the factors facilitating a successful transition for medically-released Canadian Veterans is what prompted this study.

Findings from Phase II – Qualitative Research Study

The second phase of the study used a qualitative design including two research methods: an online quantitative survey and a semi-structured, in-depth telephone interview to explore the lived experience of Canadian, medically-released Veterans who self-identified as having successfully transitioned. The qualitative design was selected by the OVO to allow in-depth conversations with Veterans in order to gain a better understanding of the transition process including what worked well and which supports best served the needs of ill and injured Canadian Veterans and their families. Based on the findings of the literature review, participants were queried on seven areas of interest as indicated in Table 2. The findings from each of these areas of inquiry will be discussed.

Table 2 – Research Areas

| Areas of Interest (From Litterature Review) |

Areas of Inquiry |

|---|---|

| Transition Process |

|

| Transition Programs and Services |

|

| Health and Disability |

|

| Employment and Education |

|

| Income and Financial Well-Being |

|

| Family, Peer and Social Support |

|

| Military Culture |

|

Area 1: Transition Process

Participants were asked questions about the transition process itself, such as how much time and preparation they had, what were the challenges, and what elements were most helpful. Questions also gathered information on which CAF, VAC or community programs the participants used.

Greatest Challenges in the Transition Process

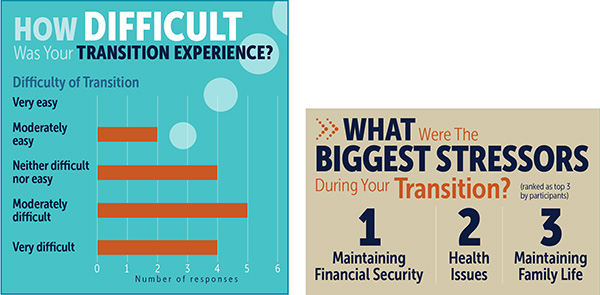

In the online survey, participants were asked about the level of difficulty of their transition experience and asked to rank the biggest stressors during their transition.

Table 3 shows that only two participants found their transition easy. The highest ranking stressors were:

- Maintaining Financial Security

- Health Issues

- Maintaining Family Life

Table 3 – Difficulty of Transition

Difficulty of Transition

How difficult was your transition experience?

Difficulty of Transition (Number of responses)

- Very easy: 0

- Moderately easy: 2

- Neither difficult nor easy: 4

- Moderately difficult: 5

- Very difficult: 4

What were the biggest stressors during your transition?

(ranked as top 3 by participants)

- Maintaining Financial Security

- Health Issues

- Maintaining Family Life

These issues were further explored during the interviews. Participants were asked to describe the greatest challenges they encountered during their transition. Five participants mentioned leaving the security and familiarity of the military. Participants remarked on how little – if any – experience they had living as adults outside of the military prior to their release. In the words of one participant, “The military was my life, my family, my everything.”

The military was my life, my family, my everything.

Five participants said the major challenges of their transition were in dealing with the bureaucracy of the CAF and VAC and obtaining the information and services needed to address their health issues. Examples included broken lines of communication between different offices; incorrect or incomplete information being given; information overload; and an inability to process the many things needed to know or do during their transition.

One participant said that planning and being proactive on their part was essential to overcoming the challenges during their transition, “You need to be proactive. You need to come to grips with the fact that you won’t be in the military all your life.” Three participants found the transition to be exceedingly challenging due to the lack of information and support provided to them, be it administrative or health support.

You need to be proactive. You need to come to grips with the fact that you won’t be in the military all your life.

Most Helpful Elements in the Transition Process

During the interviews, participants noted a variety of factors which proved, for them, to be the most helpful during their transition process. These included support from their spouse or other Veterans, and formal programs offered by the CAF.

Eight participants identified specific programs and services offered by CAF. The Second Career Assistance Network (SCAN) Seminar was mentioned as being particularly helpful five times and the Joint Personnel Support Unit (JPSU)/ Integrated Personnel Support Centre (IPSC) was mentioned four times the Vocational Rehabilitation Program for Serving Members (VRPSM) was mentioned twice.

Other participants mentioned the Veterans Transition Network, Soldier On, their base surgeon, their medical doctor, being generally proactive, therapy services on the base, and the community on the base itself as being the most helpful during the process. One participant found that the current transition process in place was sufficient to allow him to successfully transition and one indicated that having enough time to act on the information given was beneficial.

One participant noted that there were no helpful elements within the transition process and that he transitioned despite the programs and services rather than because of them.

When asked in the interview about what was the most important factor that contributed to their success, participants indicated there was a variety of factors. Five participants attributed their personal attitude and actions as the most important factor contributing to their successful transition, such as being a “realist”, “owning” and having “drive”. Five participants indicated that having a supportive family was the most important, mirroring the results from the online survey in which 13 participants found that their spouse was the greatest source of support during transition. Other factors contributing to their successful transition included their therapist, group counselling, and specific programs offered by CAF, VAC or within the community.

Planning for Transition

The online survey and the interviews posed questions concerning preparedness for the transition period. Questions included adequacy of time to prepare for release, feeling of preparation at release and if, and what, the participants received in terms of support from CAF to prepare for transition.

When asked how much time they had to prepare for transition, the answers were varied. However, there was some correlation between time to prepare and the feeling of preparedness:

- Nine of the participants felt prepared for their release. Of these, six had more than 18 months to prepare.

- The six who did not feel prepared all had less than 12 months preparation time.

I knew the release was coming, so I was willing to take the bull by the horns. I'm a self-starter and I didn't want to wait around to be told what to do.

I had plenty of time to prepare, I was able to secure a job, although it wasn't the job I wanted.

Eight participants indicated that they were not asked by anyone to consider and determine specific goals going forward. Additionally, ten participants reported that they were never encouraged to create a transition plan.

From the interviews, one participant who noted he was prepared and proactive when it came to his transition said: “I knew the release was coming, so I was willing to take the bull by the horns. I’m a self-starter and I didn’t want to wait around to be told what to do.”

One participant commented: “I had plenty of time to prepare. I was able to secure a job, although it wasn’t the job I wanted.”

Another participant who had three years to prepare said he had, “enough time to mentally prepare to leave.”

Another described the time he spent performing reduced duties as a “wading pool” which made his transition easier.

The participants who said they didn’t have enough time talked about the stress associated with leaving the military. One participant described: “I was told in six months’ time I would be released. It wasn’t really enough time because I didn’t know what I was going to do. My whole life was in the military so I really had no clue what to expect... My release was not planned.”

Don't feel that I am transitioning 'back' to civilian life but becoming a civilian for the first time.

In reflecting on how long it took to complete the transition to civilian life, nine participants said that they were still transitioning. They were not able to note a time or event in which their transition was complete, but rather they quietly began to “accept” that they were no longer in the military; and “feel” or “know” they are now a civilian. Of those who felt they were still transitioning, one went as far as to challenge the concept of transition. This participant was in the military for most of their adult life and didn’t have a civilian experience to return to, “Don’t feel that I am transitioning ‘back’ to civilian life but becoming a civilian for the first time.” For the remaining six participants the process was finite. Two said it took around one year while four found it took much longer. The longest transition period was eight years.

Area 2: Transition Programs and Services

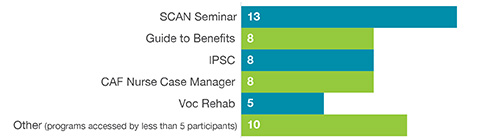

CAF Programs

During the online survey, participants were asked which CAF programs they accessed. The CAF program most accessed was the SCAN Seminar; however, only one of the three Reservists in the study attended a SCAN Seminar. All responses are shown in Table 4.

Table 4 – CAF Programs Accessed by Participants

Number of Responses (n=15)

CAF Programs Accessed by Participants

- SCAN Seminar: 13

- Guide to Benefits: 8

- IPSC: 8

- CAF Nurse Case Manager: 8

- Voc Rehab: 5

- Other (programs accessed by less than 5 participants) : 10

When asked about the effectiveness of CAF programs and services, eight participants found the programs and services effective to some degree. The responses are shown in Table 5.

Table 5 – Effectiveness of CAF Programming

Number of Responses (n=15)

Effectiveness of CAF Programming

- Very effective: 1

- Effective: 3

- Somewhat effective: 4

- Not effective: 7

During the interviews, when asked about the CAF information and services used, most participants mentioned the SCAN Seminar was useful, although they found the amount of information provided to be overwhelming. A few participants said they attended more than one SCAN Seminar. In the words of one participant, “The SCAN Seminar was a big eye opener. It’s a headful of information to digest in two days, but it’s critical.”

The IPSC was also mentioned as being a helpful environment where other military personnel understood their needs and helped to make the transition easier. As one Veteran said: “My personal experience in going to the IPSC, asking for help and having it directed in the right way was probably bar none.”

Four participants mentioned the service provided by CAF personnel in a positive light and included doctors, nurse case managers and administrative clerks. One participant said:

I worked with an administrative clerk at beginning of my transition. She saw my state of panic and gave me the best advice. She said there is a system in place that is designed to get you as healthy as possible. I don't know why, but hearing that helped to ease the process.

However, participants did point to difficult interactions related to a lack of complete or accurate information. One participant described needing to “clerk-shop,” meaning having to speak to several administrative clerks in order to gain a complete understanding of what he needed to do to prepare for release.

Negative comments were also received regarding the bureaucratic processes rather than the individuals administering the process. “It’s the machine, not the people in the machine,” one participant remarked. “There’s always going to be apathetic people, but I don’t think they’re the majority.”

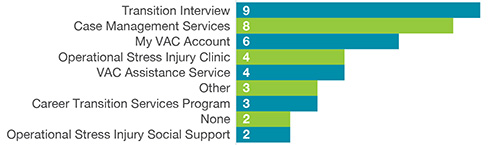

Veterans Affairs Canada Programs

Participants were asked which VAC programs they accessed, with the transition interview used most frequently.

Table 6 – VAC Programs Accessed by Participant

Number of Responses (n=15)

VAC Programs Accessed by Participant

- Transition Interview : 9

- Case Management Services: 8

- My VAC Account: 6

- Operational Stress Injury Clinic: 4

- VAC Assistance Service: 4

- Other: 3

- Career Transition Services Program: 3

- None: 2

- Operational Stress Injury Social Support: 2

When asked about the effectiveness of VAC transition programs, 11 participants found the transition programs they accessed were effective in some degree. The responses are shown in Table 7.

Table 7 – Effectiveness of VAC Programming

Number of Responses (n=15)

Effectiveness of VAC Programming

- Very effective: 2

- Effective: 2

- Somewhat effective: 7

- Not effective: 4

When asked during the interviews about the information and the services they experienced from VAC, participants who had a negative experience commented that information was provided too slowly and was incomplete or not well tailored to their circumstances. One participant described his experience:

The best example I can give you is what happened to me. I found out in June that we could receive an allowance under the Earnings Loss Benefit, which was put in place in 2010. I had no idea about this program until I found out about it in June this year. You see I left in April 2010 and in June 2016 it was a friend of mine who told me about it and when I applied for it, they told me I was eligible. All I had to do was fill out the papers and then, like magic, a very good Veterans Affairs staff member called and was very helpful. So, I can’t say anything bad about that, but it's a shame that I was not made aware of this program earlier.

This anecdote is reflected in other comments which described interactions with VAC staff in positive terms, but pointed to a system that is too slow to provide the right information at the right time.

There's a lot of information that's not getting in the right hands. I don't know why they can't assess people and tell them which program they qualify for.

Positive comments about information and the service from VAC tended to focus on positive experiences with individual case managers. As one participant remarked:

My case manager provides a lot of follow up and is always available... I feel that I can pick up the phone and ask questions, I have resources to talk to and I do not feel desperate and alone.

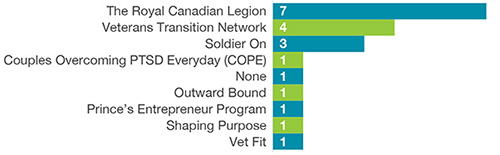

Community Programs

When asked during the interviews to describe which community programs they accessed, participants most often mentioned the Legion, followed by the Veterans Transition Network. The Legion was noted to have provided valuable assistance in learning about VAC programs and entitlements and getting help with the application process. The Veterans Transition Network was mentioned by four participants. One participant described it as “pivotal” in the success of his transition. Some participants also mentioned social media, particularly Facebook, as a source of information and connection to the wider community of Veterans. The specific community programs participants accessed are shown in Table 8.

Table 8 - Community Based Programs Accessed by Participants

Number of Responses (n=15)

Community Based Programs Accessed by Participants

- The Royal Canadian Legion: 7

- Veterans Transition Network: 4

- Soldier On: 3

- Couples Overcoming PTSD Everyday (COPE): 1

- None: 1

- Outward Bound: 1

- Prince's Entrepreneur Program: 1

- Shaping Purpose: 1

- Vet Fit: 1

Area 3: Health and Disability

Participants were asked a number of questions concerning the impact of their health con- dition(s) on their daily life or ability to participate fully in transition programs. They were also asked about the adequacy of support they received from CAF and VAC and how they experienced the transition to the provincial health care system.

Impact of Health Condition(s)

Five participants were medically-released for a physical health condition, three for a mental health condition and seven for a combination of both conditions. At the time of release, 11 participants noted that their VAC benefits were in place, and nine participants indicated that the number of health conditions they were being compensated for by VAC had increased since their release.

Participants were asked if their health condition had created a barrier to their daily activities, and if so, which of the activities were challenging. The responses are shown in Table 9.

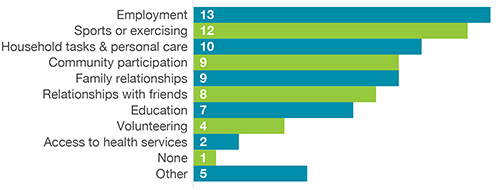

Thirteen participants indicated that employment was the most challenging activity. This was closely followed by sports or exercising and performing everyday household tasks. Only one participant indicated that they had no barriers to daily activities.

Table 9 – Most Challenging Activities as a Result of the Health Condition

Most Challenging Activities as a Result of the Health Condition

- Employment

- Sports or exercising

- Houselhold tasks & personal care

- Community participation

- Family relationships

- Relationships with friends

- Education

- Volunteering

- Access to health services

- None

- Other

The other activities specified included trouble sleeping, social activities and self-image and confidence issues.

Adequacy of Medical Support from CAF and VAC

During the interviews, participants were asked about the medical support provided by the CAF and VAC to manage their health conditions. Comments from participants were varied and there were issues raised with both CAF and VAC supports.

Three participants pointed to negative experiences they had with CAF medical personnel. These included a participant who sought help from a civilian psychotherapist (not covered by CAF) because he did not feel that the CAF psychiatrist listened or supported him. Another participant found that CAF medical personnel misdiagnosed his injuries, resulting in difficulties obtaining support and care from VAC after his release.

Those who experienced difficulties with obtaining support from VAC said VAC was slow to provide support or provided inadequate support. The comments included complaints that VAC failed to acknowledge the extent of their injuries, resulting in a protracted struggle to obtain care, to complaints about slow bureaucratic processes and long delays before being assigned a case manager. The comments below highlight these experiences.

It was a fight to get VAC to acknowledge the full extent of my injuries. Immediately after my transition out of the CAF and onto full coverage by VAC, I had to launch two appeals - both of which I won. The fact that I had to launch those appeals within a month of being their client was telling.

I was only appointed a VAC case manager six months ago even though I released two and a half years ago. It would have been useful to have had a case manager when I was released.

The support was also found to be positive in some areas but negative in others. As one participant said: “VAC approved coverage for physiotherapy, crutches and such. It takes a while to get provincial coverage, so support from the VAC was helpful.” However, this participant was “surprised” to be denied coverage for other “basic stuff” such as the costs associated with transportation to his surgeries.

Transition to Provincial Health Care System

When asked about their transition from the CAF health care system to the provincial health care system following their release, eight participants described challenges in finding a family physician and having to wait for care at walk-in clinics. As one participant said:

It took two years to find a family doctor. In the meantime, I had to go to a walk-in clinic... You have to get there at 6:00 am and you still wait in line.

Another participant described a similar experience, but also mentioned the challenge of bringing his civilian doctor “up to speed” on his medical issues. One participant pointed to long wait times for access to specialty care, saying that he is still on a waiting list to access a chronic pain clinic.

Four participants noted having a positive experience in the transition to the provincial health-care system. Two mentioned having applied for their provincial health-care card well before their release date while another (a Reservist) had kept their civilian doctor and health card instead of joining the military health system. One participant described himself as “lucky” that his wife had a family doctor who was accepting new patients.

Others described the care provided from the provincial health-care system as not of the same quality that was provided by the CAF. “Having PTSD, I felt excluded and not well cared for,” said one participant. “There seems to be a lack of caring on the civilian side.”

Area 4: Employment and Education

The survey gathered information about current employment status. Eight participants were employed at the time of the study, and six of the eight indicated that they were satisfied with their current occupation and the number of hours they worked each month. Five were working full-time and three part-time. Seven participants were either unemployed (two) or not seeking employment (five).

The interview posed questions around the participants experience obtaining employment post-release, the challenges they faced and what was helpful, including their experience participating in vocational rehabilitation programs or further education post-release.

Experience obtaining Employment Post-Release

During the interviews, participants offered various perspectives on their experience obtaining and searching for employment. Challenges that created difficulty for participants to find employment included their health condition, lack of formal qualifications, age and lack of available or suitable work. Those who did pursue employment following their release cited the difficulty in “selling” their military skills and experience to civilian employers. One participant pointed to the fact that since he joined the CAF at 18 years of age, he had never applied for a civilian job in his life. Other participants said they did their best to “civilianize” their resumes, but said it would have been helpful to have had a course on how to write a civilian resume. Another participant said that his age was a particular challenge: “The competition for jobs is extremely high. It’s stressful to go into interviews where you’re the oldest person.”

Participation in Vocational Rehabilitation Program

Among the participants who pursued vocational rehabilitation, most had experience with the Service Income Security Insurance Plan (SISIP) Vocational Rehabilitation Program. Two individuals who participated in the SISIP program said they ended up dropping out because of their health. One participant said his experience with SISIP was not helpful. He said they did an assessment that recommended work at an engineering firm as his university degree was in engineering. However, he believed that they failed to account for his lack of technical experience which would put him at a significant disadvantage in terms of salary potential.

Eight participants also mentioned participating in the VRPSM during their final months prior to release. One of these participants used this experience as a bridge to a Public Service position. On the VAC side, five participants participated in the Rehabilitation Services and Vocational Assistance Program with one participant describing their experience as “astonishing and outstanding.”

Further Education/Retraining Post-Release

When asked about their experiences obtaining education or training after release, nine participants said they had no need or interest in pursuing further education or training (five participants), or that their health condition limited their ability to do so (four participants). Those who said their health condition limited their ability to obtain education or training after release mentioned issues with chronic pain and concentration due to mental health challenges.

Area 5: Income and Financial Well-Being

Adequacy of Disability Benefits

In the survey responses, nine participants indicated they had access to benefits under the NVC, one under the Pension Act and five under both the NVC and the Pension Act. During the interview, ten participants said that their disability benefits were sufficient, specifically pointing to the VAC disability pension to ensuring their life-time financial stability. Four participants mentioned that they received the VAC disability award near the time of release; however, while one noted the award to be “substantial,” another stated that the award is “all gone.”

Three participants mentioned that VAC disability benefits were not adequate. One participant stated that some injuries should be compensated “above and beyond” what certain rules suggest, and another felt that the compensation was not fair due to the difficulty of the transition process. Furthermore, one participant noted that because of being deemed capable of working, he is not eligible for full VAC income support benefits.

Satisfaction with Financial Situation

Participants were asked to describe their financial well-being. The responses are shown in Table 10.

Table 10 – Financial Well-Being

| Question (n=15) | Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I could handle a major unexpected expense | 2 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 1 |

| I am securing my financial future | 2 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 0 |

| I struggle to make ends meet | 0 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

Participants were nearly unanimous in their current financial satisfaction; 14 indicated that they now felt satisfied with their financials. Sentiments such as feeling “very satisfied,” “lucky” or “fortunate” were used to describe their current financial situation. However, eight of these 14 participants also described anxiety about their financial future at the time of release. Several comments highlighted this concern:

Financial security after release was a significant issue – we are a single income family.

Some of my angst was financial…Having financial security, it’s night and day.

The big fear that all the military people have when they leave is the money.

One Veteran, who served 21 years and is not employed, noted dissatisfaction with his financial well-being. He expressed concern with making ends meet and the potential impact of any unexpected future expenses.

Only three participants indicated that they were not in receipt of a Canadian Forces Superannuation Pension benefit.

Area 6: Family, Peer Support and Social Support

Importance of Spouse / Other Family

Participants were asked to rank who they considered to be their most important source of support during their transition. Thirteen participants were married at the time of their release and 12 said that their spouse was an integral part of the transition process. One participant wished, in hindsight, that their spouse had been more involved in their transition noting “if I had been better advised, I would have had my spouse attend more (pro- grams) during the transition.”

Greatest Sources of Support

The top three most important sources of support were:

Greatest Sources of Support

What were your greatest sources of support?

(number of times ranked top 3 by participants)

- Spouse: 13

- Therapist, Counsellor or Psychologist: 8

- Friends & Children: 6

Participants were asked what CAF programs their spouses accessed during their transition. The responses are shown in Table 11.

Table 11 – CAF Programs Accessed by Spouse

Number of Responses (n=15)

CAF Programs Accessed by Spouse

- None: 5

- SCAN seminar: 5

- Attendant Care Benefit: 2

- CFMAP: 2

- Other (6 programs): 6

Participants were asked what VAC programs their spouse accessed during their transition. The responses are shown in Table 12.

Table 12 – VAC Programs Accessed by Spouse

Number of Responses (n=15)

VAC Programs Accessed by Spouse

- None: 11

- Case Mgmt. Services: 2

- Other: 1

- OSISS: 1

Role of Veteran Associations/Peer Groups

The majority of participants remained engaged within the Veteran community post-release. Thirteen participants noted various channels through which they interacted with peer groups and Veteran Associations. Eight of these participants felt that other Veterans could better understand their military experience, help them cope with transition and recommend programs and activities. As articulated by one, “When everything is going wrong and you lift a flag, these guys are right there.” The Legion was noted as helpful with understanding how “to navigate the system,” providing information on the supports available and preparing and submitting applications. Five participants maintained informal networks with other Veterans, such as colleagues, former military friends, or other social groups. Two had spouses or other family members that were Veterans. One participant felt that through Facebook they could find Veterans groups or stay in contact with former acquaintances. On the other hand, one participant said he deliberately eschewed other military members after release: “I didn’t want anything to do with other military members.”

Participation in Group Programs for Veterans

Five of the nine participants that took part in group programs identified the Veterans Transition Network as being very helpful. This program, offering group counselling and role-playing, was described as “life changing” by some participants. Other group programs identified by participants as being helpful included the Outward Bound Veterans Program, Soldier On, Shaping Purpose, Vet Fit and Guitars for Vets.

Making/Maintaining Civilian Relationships

Five participants reported difficulties with forming civilian relationships. They felt that civilians did not understand their experience or they mentioned a lack of trust of civilians. As expressed by one participant, “we were immersed in military culture for a long time” or “in the military, we have our own way of seeing things, our own way of life.” Five participants who did not have difficulty establishing civilian relationships noted that they had made an effort to move on from the military culture and get involved in their neighbourhood and community.

Area 7: Military Culture

Stigma

Nine of the participants indicated that the stigma associated with their injury was a factor during their transition. These participants indicated that they delayed or avoided discussing their mental or physical condition while in the CAF due to the stigma prevalent in military culture. Comments related to stigma highlight this issue:

There is a mindset in the military to suck it up and get on with it.

I was in meetings and people would talk about ‘those guys with PTSD…'

When I returned from […], I knew I was changed as a human being. I also knew that if I said anything, that I would be negatively judged and made fun of.

Seven specified that they were reluctant to disclose or obtain treatment due to the perceived affect it would have on their career as their colleagues and superiors would have a negative perception of them. These participants felt that the time spent in treatment was detrimental to their career:

As soon as I asked for help, my career was put on hold.

Not so much afraid to seek help, but afraid to compromise career.

The common belief is that if you come forward with PTSD you will be released, and that is not true.

You feel like everybody is looking at you differently.

Recognition

Two participants indicated that their release would have resulted in a better transition outcome if they had received a ceremony to recognize their service. For one, the release date was two days prior to a full 12 years of service. This Veteran felt that receiving the Canadian Forces Decoration, awarded after 12 years of service, would have obliged a final and appropriate recognition of service. Another Veteran would have liked to have received a “Depart with Dignity” ceremony that would have involved receiving a flag or other form of recognition.

Finding Purpose after Military Service

For 12 participants, finding a new sense of purpose after their military service represented a significant challenge since they had spent most of their adult lives within the military and had little experience finding work or even making and maintaining friendships outside of the military context. As noted by one participant, “you can take the guy out of the military but you can’t take the military out of the guy.”

Participants mentioned difficulty adjusting to life after military service and transitioning away from a structured and demanding career. They described the challenge was in separating their identity as serving members, often formed over entire adult lives, from their own personal self, and realizing they have potential outside the military.

Four participants found that by helping other Veterans and their families and through volunteering, they were provided with a new sense of purpose and self-worth:

My new chapter is volunteering and taking care of other Veterans, starting a program to help families.

It is advocating for Veterans that has really helped keep me connected with the broader Veteran’s community and provided me with that purpose.

While I was proud to be in the military, I couldn’t find that purpose and drive elsewhere […] I was able to work through it and find my passion in going back to school and helping other Veterans.

One participant described their new found sense of purpose: “Who I am isn’t necessarily tied to what I did in the military.”

Summary and Conclusions

Phase I of the research, the literature review, highlighted the requirement for more independent research on the transition experiences of Canadian Veterans and on the medically-released Veteran population post 2006, to better understand the effects of the NVC on successful transition outcomes.

Phase II explored what contributes to a successful transition using an online survey and in-depth telephone interviews. Fifteen Veterans, who were medically released between 2006 and 2014, and who identified as having successfully transitioned, participated in this phase. Their answers allowed for an in-depth analysis of the lived experience of medically-released Canadian Veterans. The research areas of interest provided insight into both contributors and challenges.

The factors contributing to a successful transition from military to civilian life were:

- Being proactive and “owning” their transition;

- Having a supportive spouse was vital and noted as being the greatest source of support. Finding ways to increase the involvement of spouses in the transition process was recommended as many of the participants’ spouses did not access any transition programming, particularly with VAC; and,

- Planning ahead for the transition. SCAN seminars were noted as a helpful tool to prepare for their financial security and life outside the military. Some wished they had taken the SCAN seminar earlier in their career so that they could have been better prepared for release when the time came.

The challenging factors included:

- Finding a new sense of purpose outside of the military, finding a new or different way to serve and be of value to their community;

- Stress towards maintaining financial security. Being able to equate military experience with civilian work experience is an essential ability for many in order to secure employment post-release; and,

- Stigma towards injuries, particularly mental health. Participants described a reluctance to ask for help with mental health challenges or participate in certain programs because of what others may think of them or the perceived impact it would have on their military career. Not seeking help made transition more difficult.

- While not necessarily a challenge, some found that there was no time or event in which their transition was complete. Rather, they had begun to accept the adjustment to civilian life.

The results of Phase II confirm the findings of Phase I and showed that there were similar areas in the transition process that needed to be addressed. While the literature review was not focused solely on medically-released Veterans, as were the online survey and the in-depth interviews, the importance of preparation and planning, including family members in the transition planning, and realizing and addressing the stigma of mental illness, were all noted to be required for a successful transition. Additionally, the results of the online survey and in-depth interviews echoed the findings of the LASS 2016 survey conducted by VAC. A large portion of respondents (32%) reported difficulty with their transition in the LASS survey; the Phase II findings noted that nine of the 15 had some degree of difficulty.

Insight into the lived experience of medically-released Veterans and the programs and services that Veterans feel most contributed to their successful transition provides information to help improve and tailor the supports provided to medically-releasing CAF members, Veterans and their families. The results of the online survey and the in-depth interviews illustrate that all facets of the transition can be challenging, depending on the situation of the released member, as noted by the varied positive and negative experiences of each individual participant.

The release process was unique for each Veteran who participated in this research study. As the first qualitative research study on the determinants of successful transition of medically-released Canadian Veterans, the results of this study could inform other Canadian research efforts. The study will drive the OVO’s future research on transition including, potentially, a focus group with family members. The objective being to better understand their transition in order to improve all services and programs for our Veterans and their families.

Appendix 1 – Screening Questionnaire

Thank you for indicating your interest in participating in the OVO Determinants of Successful Transition project Please complete the following screening questions:

Contact Information:

Name:

Telephone:

Email:

Screening Criteria:

- Did you medically release between 2006 and 2014?

- Yes

- No

- Do you feel that you successfully transitioned?

- Yes

- No (if no, please briefly elaborate): ____________________

- What is your gender?

- Male

- Female

- Is your service Regular, Reserve or both?

- Regular

- Reserve

- Both

- At release, were you an Officer or Non-commissioned member (NCM)?

- Officer

- NCM

- How many years of service did you complete prior to releasing?

- Less than 10 years

- 10 years or more

Thank you for your participation. An OVO researcher will contact you within a week.

Appendix 2 – Online Survey

Section 1 - Demographic and Service Related Factors

- What is your age?

- Less than or equal to 30 years

- Between 31 and 40 years

- 41 years and over

- What is your gender?

- Male

- Female

- What is your current marital status?

- Single

- Married

- Separated

- Divorced

- Common Law

- What is the highest level of formal education you have completed?

- Some high school

- High school Diploma

- College Diploma

- Bachelor’s Degree

- Master’s Degree

- Other Graduate Degree

- Province of residence

- Alberta

- British Columbia

- Manitoba

- New Brunswick

- Newfoundland and Labrador

- North West Territories

- Nova Scotia

- Nunavut

- Ontario

- Prince Edward Island

- Quebec

- Saskatchewan

- Yukon

- Province of residence at release

- Alberta

- British Columbia

- Manitoba

- New Brunswick

- Newfoundland and Labrador

- North West Territories

- Nova Scotia

- Nunavut

- Ontario

- Prince Edward Island

- Quebec

- Saskatchewan

- Yukon

- How many years of service did you complete prior to releasing?

- 10 years or less

- Between 11 and 20 years

- Over 20 years

- Did you serve in the Regular, Reserve or both forces?

- Regular

- Reserve

- Both

- In what branch of the CAF did you serve?

- Army

- Navy

- Air Force

- More than one

- What was your rank at the time of release?

- Officer

- Non-commissioned member

- How many more years were you planning on serving in the CAF if you had not been medically released?

- 0 years

- 1-5 years

- 6-10 years

- 11-15 years

- More than 15 years

Section 2 – Transition Process

- In general, how difficult or easy was your transition experience?

- Very difficult

- Moderately difficult

- Neither difficult nor easy

- Moderately easy

- Very easy

- Did you complete a Veteran Affairs Canada (VAC) transition interview prior to release?

- Yes

- No

- Did anyone ask you to consider your goals going forward from military life or provide you with assistance in doing this?

- Yes

- No

- Did anyone encourage you to create a transition plan?

- Yes

- No

- How much time did you have to prepare for release once you knew you were going to be medically released?

- Less than 3 months

- Between 3 and 6 months

- Between 6 and 12 months

- Between 12 and 18 months

- Between 18 and 24 months

- More than 24 months

- Did you feel prepared for your release?

- Yes

- No

- How effective was the transition programming you received through CAF?

- Not effective

- Somewhat effective

- Effective

- Very effective

- Which transition related programs or services did you access within CAF to help prepare for your release? (Select all that apply)

- SCAN seminar

- Base Personnel Selection Officer

- Vocational Rehabilitation Program for Serving Members (VRPSM)

- Education Reimbursement for Primary Reserves

- Integrated Transition Plan

- CAF Nurse Case Manager

- Integrated Personnel Support Centres (IPSC)

- Guide to Benefits, Programs and Services for Serving and Former Canadian Armed Forces Members and their families

- Military Family Resource Centres (MFRC)

- Other (please specify): ____________________

- None

- How effective was the transition programming you received through VAC in terms of directing you to appropriate resources that were offered through VAC?

- Not effective

- Somewhat effective

- Effective

- Very effective

- Which transition related programs did you access through VAC? (Select all that apply)

- Transition Interview

- My VAC Account

- Career Transition Services Program

- Vocational Assistance

- VAC Assistance Service

- Operational Stress Injury Social Support (OSISS)

- Operational Stress Injury (OSI) Clinic

- Case Management Services

- Other (please specify): ____________________

- None

- Did you access transition related programs or services that were offered in the community by non-profit groups or other levels of government?

- Yes (please specify): ____________________

- No

- In general, how effective were the transition programs and services you received through community resources?

- Not effective

- Somewhat effective

- Effective

- Very effective

- Non-applicable (if answer to 11. was No)

- Which of the following did you find to be the most stressful during your transition? Please rank the following items from Most Stressful (1) to Least Stressful (6). If the option Other does not apply, please ranks as Least Stressful (6).

- Health issues

- Maintaining financial security

- Maintaining family life

- Engaging with friends or peer groups

- Being understood by civilians

- Other (please specify, if applicable): ____________________

Section 3 – Health & Disability

- How would you describe the type of illness or health condition that was the reason for you being medically released?

- Physical health

- Mental health

- Combination of both

- Were your Veterans Affairs Benefits in place at the time of release?

- Yes

- No

- Has the number of health problems you are currently being compensated for or receiving health services through VAC for increased, decreased or stayed the same since the time of your medical release?

- Increased

- Decreased

- Stayed the same

- Have you received a formal diagnosis or treatment from the Provincial healthcare system for any additional health condition that you are not receiving benefits, programs or services from VAC?

- Yes

- No

- Would you say that your health condition has created a barrier to daily activities? If so, which activities would you say have been challenging for you? (Select all that apply)

- Performing every day household tasks and personal care

- Employment

- Community participation (recreational or community activities)

- Sports or exercising

- Education

- Access to health services

- Family relationships

- Relationships with friends

- Volunteering

- Other (please specify): ____________________

- None

Section 4 – Employment and Education

- What is your current employment status?

- Employed

- Unemployed

- Not seeking employment

- If you are employed, please answer the remaining questions in Section 4. If not, please skip to Section 5.

- Are you generally satisfied with your current occupation?

- Yes

- No

- Do you work part-time or full-time?

- Full-time

- Part-time

- Are you satisfied with the number of hours of work you get each month?

- Yes

- No

- Have you completed or are currently completing any formal education programs since you were medically released?

- Yes

- No

Section 5 – Income and Financial Well-being

- Have you received benefits, programs or services through: the Pension Act, the New Veteran’s Charter (NVC), a combination of the Pension Act and NVC?

- Pension Act

- New Veteran’s Charter

- Combination of both

- Which benefits did you receive? (Select those that apply)

- Service Income Security Insurance Plan Long Term Disability

- VAC Disability Pension

- Attendance Allowance

- Exceptional Incapacity Allowance

- Earnings Loss Benefit

- Permanent Impairment Allowance

- PIA Supplement

- Disability Award

- Veterans Independence Program

- Family Caregiver Relief Benefit

- Other (please specify): ____________________

- None

- Are you in receipt of CFSA Pension benefits?

- Yes

- No

- Describe your feelings towards your financial well-being:

- I could handle a major unexpected expense

- Always

- Often

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I am securing my financial future

- Always

- Often

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I struggle to make ends meet

- Always

- Often

- Sometimes

- Rarely

- Never

- I could handle a major unexpected expense

Section 6 – Family, Peer Support and Social Support

- What were the most important sources of support for you during the transition process? Please rank from Most Important (1) to Least Important (8). If the option Other does not apply, please rank as Least Important (8).

- Spouse or significant other

- Children

- Parents

- Friends

- Veterans Support Group

- Therapist, counselor or psychologist

- Service animal

- Other (please specify, if applicable): ____________________

- In what CAF transition programs or services did your spouse or family members participate in during the pre-release period? (Select all that apply)

- SCAN seminar

- Integrated Personnel Support Centres (IPSC)

- Operational Trauma and Stress Support Centres (OTSSCs)

- Operational Stress Injury Social Support (OSISS)

- Military Family Resource Centres (MFRC)

- CF Spousal Education Upgrade Benefit

- Attendant Care Benefit

- Caregiver Assistance Benefit

- Military Families Fund

- Family Liaison Officer

- Family Information Line

- Canadian Forces Member Assistance Program

- You’re Not Alone – Guide to Connecting Military Family’s to Mental Health and Social Wellness Programs

- Mind’s the Matter

- Youth with Parents who have Experienced Trauma

- Other (please specify): ____________________

- None

- In what transition programs or services did your spouse or family members participate in that were offered through VAC during the post-release period? (Select all that apply)

- VAC Transition Interview

- Vocational Assistance

- VAC Assistance Service

- Family Care Relief Benefit

- Operational Stress Injury Social Support (OSISS)

- Operational Stress Injury (OSI) Clinic

- Pastoral Outreach

- Case Management Services

- Other (please specify): ____________________

- None

- Did your spouse or family members participate in any transition related programs or services that were offered in the community through non-profit groups or other levels of government?

- Yes (please specify): ____________________

- No

Appendix 3 – Interview Guide

Introduction

Thank you for participating in our research study being conducted by the Office of the Veterans Ombudsman (OVO) with contract support from EKOS Associates.

The purpose of this study is to determine the factors during the release process that facilitate a successful transition and integration into civilian life for medically-released Canadian Armed Forces members. While you may not directly benefit from this study, a common understanding of the factors which result in successful integration into civilian life is essential to ensure that the processes, programs and services are in place to achieve a successful transition and to monitor and measure effective outcomes on a continuous basis.

This interview should take approximately 45 minutes. This study includes questions about your experience during transition to civilian life, including your challenges and positive experiences.

Your participation in this study is voluntary. You may skip any question that makes you uncomfortable or that you do not wish to answer, and you can stop or pause the interview at any time.

If you wish to withdraw, you will be exempt from further questioning. You will then be asked if the information up until the point of withdrawal may be used in the study.

Your identity will remain confidential throughout this study. Lastly, do you give your consent to have the interview recorded?

Transition Process

- In general, could you tell me about your transition experience? What were some of your greatest challenges, and what were the things that helped you most?

- (Planning) Could you tell me about the things the CAF encouraged you to do to prepare for transition?

- Probes: What can you say about the information that was given to you (or not given to you) during the transition process? Was it helpful, did you feel like you got it at the right time? What information do you wish you had been given but was not given to you?

- Probes: How did your goals or values effect your transition planning?

- Probes: What can you say about the CAF personnel who helped you? Did you find that they were knowledgeable and helpful? What was the most helpful thing that they did that helped you during this time? What could they have done that would have helped you more?

- (Adequate preparation time) Could you tell me a bit more about the time between when you knew you were going to be medically released and the time you were actually released? What was that time like for you? Did you have enough information to plan for your release? Did you feel like you had an adequate amount of time to plan or prepare for civilian life? If not, what would have been more helpful and why?

- (Stigma). Some military members say that they did not ask for help with certain health challenges or participate in certain programs because of what others might think about them if they did. Looking back, was this a factor in your transition process? If so, how?

- Probes: Were there any programs or services that you wish you had taken advantage of but did not participate in because you were concerned about what others might think about you?

- Could you tell me about what VAC personnel encouraged you to do during the transition process (before or after release). What could VAC have done better to help you transition more effectively? At what point in the release process did you engage with VAC? Was this early enough?

- Probes: What can you say about the information that was given to you (or not given to you) during the transition process? Was it adequate, helpful, did you feel like you got it at the right time in the transition process? What information do you wish you had been given (but were not).

- Could you tell me about any community based programs, services or resources that you accessed that were especially helpful? Which of these most helped you and why?

- Probes: Did you access any web-based resources, apps, or social media sites that were particularly helpful to you? If so, what were they and why were they helpful?

- (Impact of military culture) Some people have said that the most important part of a successful transition was finding new meaning and purpose in life after military service. Was this a part of your transition experience and if so, what was it that helped you find a new sense of meaning, purpose or direction? How much of a factor was this in your transition process and what helped you with this cultural transition?

Health & Disability

- Tell us about the help you were given to manage your health condition by CAF and VAC. What was most helpful to you during this process?

- Probes: Do you feel that you have been given adequate tools to help you manage your health condition? If not, what is missing or what would help?

- Please tell us about your transition from the CAF healthcare system to the Provincial healthcare system. Was this a smooth transition or were there some challenges accessing services? What was most helpful to you during this process?

- (Ability / disability) Have you felt like your health condition has prevented your full participation in rehabilitation programs or civilian society in any way? If so, how would you describe any barriers you have encountered as a result of your health condition? What supports or assistance have you received to overcome these barriers, and what has been the most important thing that has helped you increase your full participation in community life?

Employment and Education

- How would you describe your experience finding employment after your release? Did you face any difficulties in finding employment after your release? What were those?

- Probes: What was most helpful to you in finding work after release?

- Probes: If not in the labour force, ask them to elaborate on why they are not seeking employment or what they feel would help them have more of a chance in the labour market.

- Did you participate in any vocational rehabilitation program before or after release?

- Probes: If yes, what was the most helpful part of these services for you? What do you think would have been more helpful? Do you feel that the services provided by DND or VAC adequately helped you to identify transferrable skills that are in demand in the civilian workplace?

- Probes: If no, was there a reason you were not able to access these services?

- Did you receive further education or retraining after release?

- Probes: If yes, what was this experience like for you? Was this helpful for obtaining meaningful employment after release? Why or why not?

- Probes: If no, were there any reasons that you did not take post-service education? If so, was there anything missing that would have helped you to engage in post-service education?

- (Ability / disability) To what degree have health conditions related to your military service been a barrier in the civilian labour force?

- Probes: Has your current employer made adequate accommodations for any health-related concerns that impact your ability to fully participate in the workplace or are you still experiencing barriers? What has been helpful during the process of settling into a new job and ensuring any health conditions are accommodated appropriately?

Income and Financial Well-being

- Describe your level of satisfaction with your current financial situation?

- Probes: How much of a factor is this in your feelings about how successful your transition from military to civilian life has been?

- Do you feel that your earning potential is affected by your health condition, and if so, do you feel like your VAC disability benefits adequately makes up the difference between what you earn and what you earned at the time of your release from the military?

Family, Peer Support and Social Support

- What can you tell us about the importance of the role that your spouse or family played in the transition process?

- Probes: How much were your family members involved in your pre-release information sessions or programming?